A Significant Decline in Satisfaction with EU Membership

The Czech Republic joined the European Union in 2004 following a referendum in July 2003, in which 77% of those voting were in favor of accession. The referendum was preceded by a campaign, and after a long period of accession talks, expectations were relatively high. Since then quite a few of the expectations have been met and some unrealistic notions have been cleared up, but there have also been some disappointments.

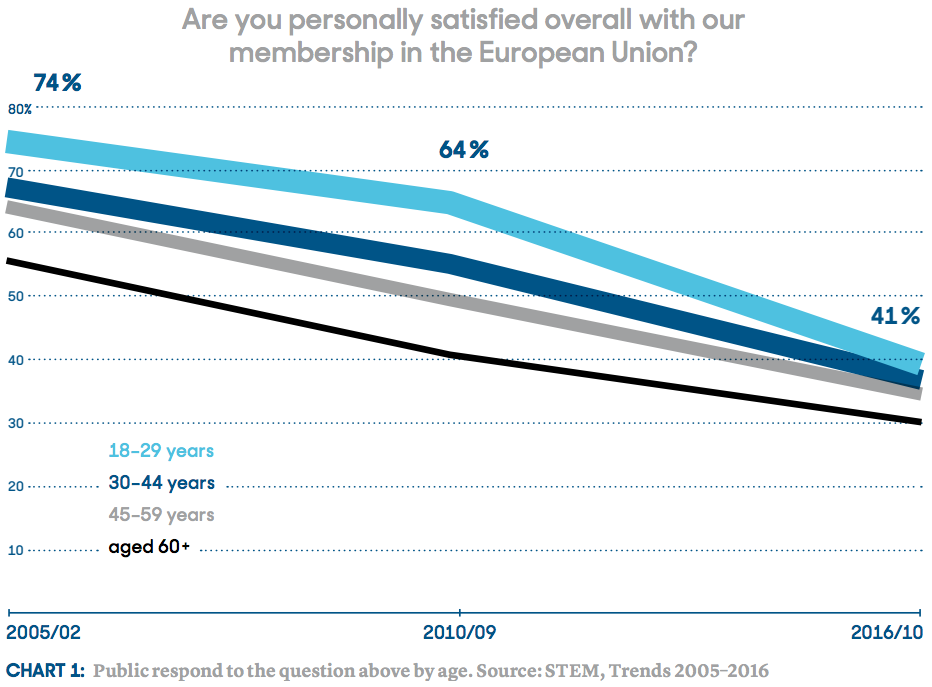

Satisfaction with EU Membership Among the Czech Public has Generally Shown a Downward Trend. What is the Breakdown by Age?

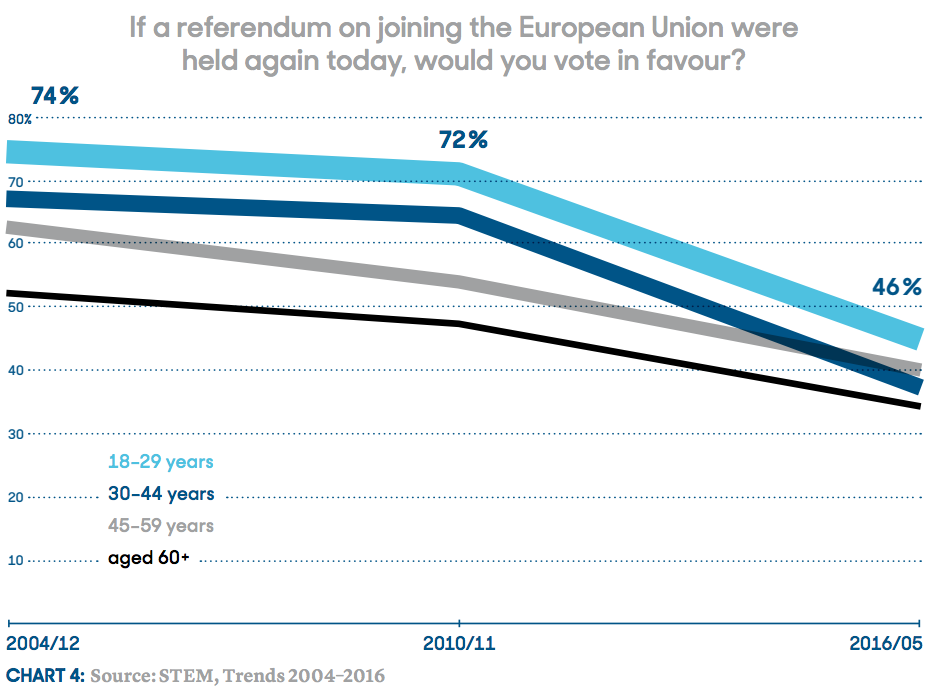

In 2005, a clear majority of young people was satisfied with EU membership (74%, compared with 54% among those over the age of 60). However, this majority view has gradually been declining, particularly since 2012, i.e. over the same period where our data also shows a growing general dissatisfaction with the political situation in the Czech Republic.

Ironically, this decline happened just before a government proclaiming itself pro-European came to power, and on the eve of the election of a president who also described himself as pro-European. Although these victories briefly reversed the trend, they did not arrest the tendency overall. On the contrary, this has continued to the present day and, if anything, has accelerated. Our research shows that only a minority of young people (41%) is satisfied with the EU membership. Nevertheless, this proportion is still higher than in other age groups.

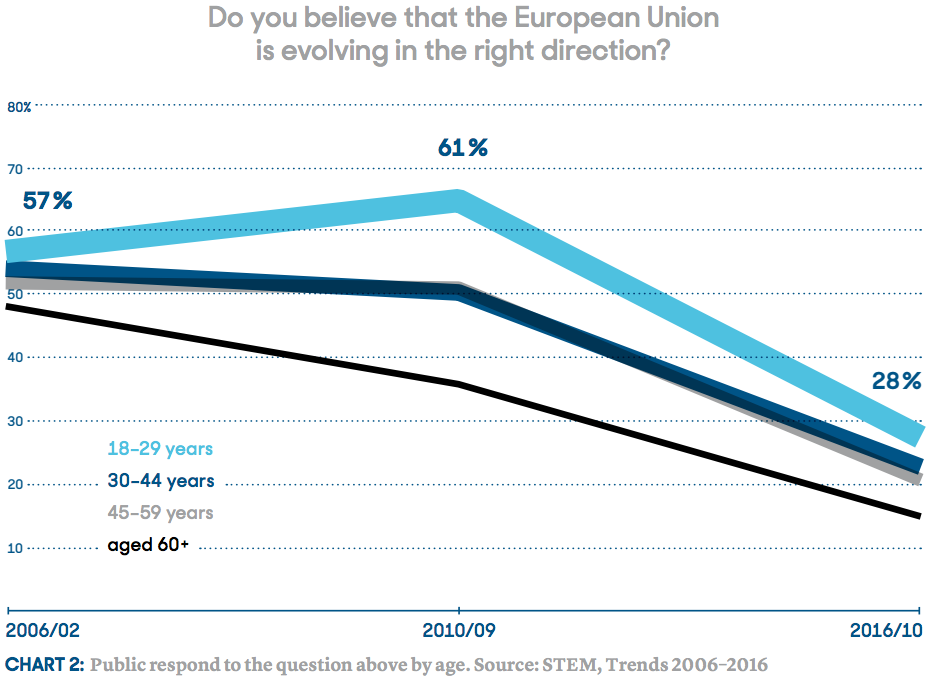

Is the EU Evolving in the Right Direction?

On the whole, Czech public opinion regarding developments in the EU has been quite reserved. When asked whether the EU is evolving in the right direction, the positive response has almost halved compared with the original. This includes the younger generation, which in the past responded much more positively than the rest of the population.

The highest ratings among young people (defined here as those under 29) were recorded in 2009 and 2010 (in the region of 69%). Most recent polls (since October 2016) show that only one quarter (28%) of respondents in this age range believes the EU is “evolving in the right direction.”

What made positive attitudes peak specifically in 2009 and 2010? The European Council Presidency, held by the Czech Republic in 2009, must have played a role, with Europe and European integration a frequent topic of discussion and many young people having an opportunity to participate in the debate in one form or another. Many factual arguments were presented in political debates and the importance of European integrity was stressed by authoritative figures. The Czech Republic was riding high, and people had literally embraced the EU integration.

The oldest generation scores at the opposite end of the opinion spectrum. Their initial response to the same question was in the region of 47%, culminating in the same period as among young people, i.e. in 2009 (55%) and 2010 (53%). Since then we have seen a slow decline, which has accelerated recently, until it dropped to the present paltry 14%.

For the first time since the beginning of our research the ratings fell below 20 percentage points. Why is this happening now and why specifically among senior citizens? What aspect of EU development have they failed to find convincing? Is it possible that current developments have rekindled some historical resentments? Or has the present-day European Union failed to respond sufficiently to their concerns and political priorities? This issue is worthy of a more detailed analysis, in terms of the attitudes to NATO and the EU among not only the older generation but also among other groups.

The overall picture is summed up by the graphic, which shows how the public responded to the question below.

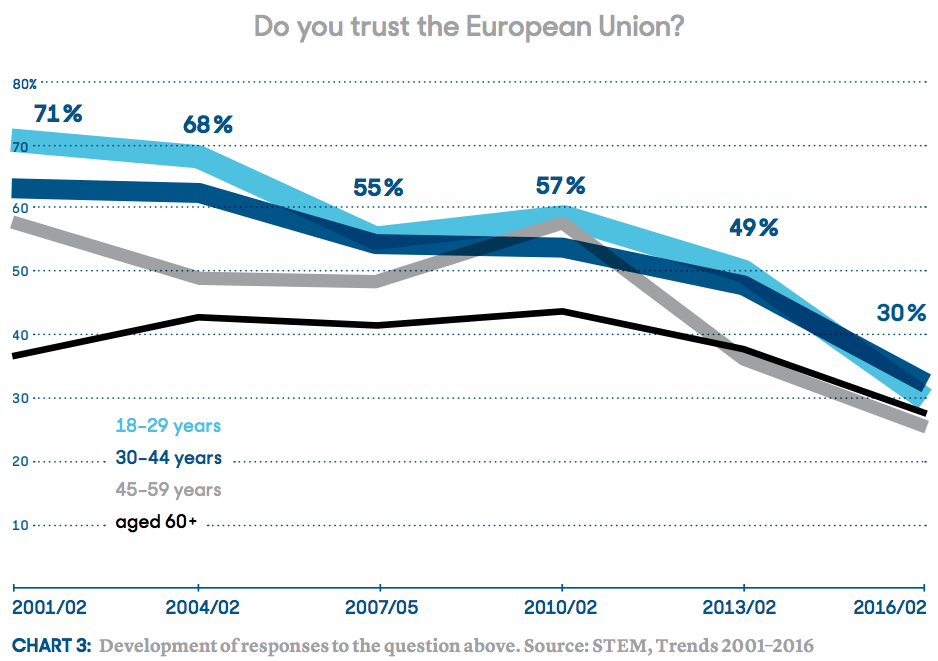

Trust in the EU has Declined in All Age Groups

Over the past fifteen years, the support for EU membership has developed in a way which, without a shadow of a doubt, points in the same direction. Support for EU membership among the Czech public has waned considerably.

This development has affected all age groups without exception, but the decline has been most striking among the young: trust in the EU has gone down from the original 71 percent to a mere 30 percent of respondents. By comparison, trust has also declined among the oldest age group, i.e. senior citizens, only less drastically: by 10 percentage points in the course of the period studied.

Another striking feature of this development is a strong convergence between the attitudes of various age groups. Does this mean that a cross-generation consensus is emerging on the issue?

A more detailed examination of the issue that takes into account other data shows that whereas in terms of age a consensus has indeed emerged, responses to the question regarding trust in the EU continue to differ depending on educational levels. This shows that differences in terms of educational levels have not been affected: while the number of EU supporters has declined among people with all levels of educational attainment, the decline has followed a similar pattern in all these groups.

The Young are Still Willing to Vote in Favor of EU Membership

A differently phrased question—how would the public respond were a referendum on the Czech Republic’s membership in the European Union to be held now—reveals a downward tendency across all age groups. The highest level of support among senior citizens was recorded in the autumn of 2005: 55 percentage points. Since then the support has been declining and currently stands at 33 percent. The youngest generation started out with a high level of support (74% in 2004), falling below 50 percent by September 2015.

Factors that helped accelerate the downward trend include the long-term refugee crisis and anticipation of the outcome of the Brexit referendum, which the Czech public followed with great interest. Nevertheless, if a referendum on EU membership were to be held now, young people would still be more likely to vote in favor—46 percent according to the survey conducted in May 2016, as shown in the graphic (chart 3).

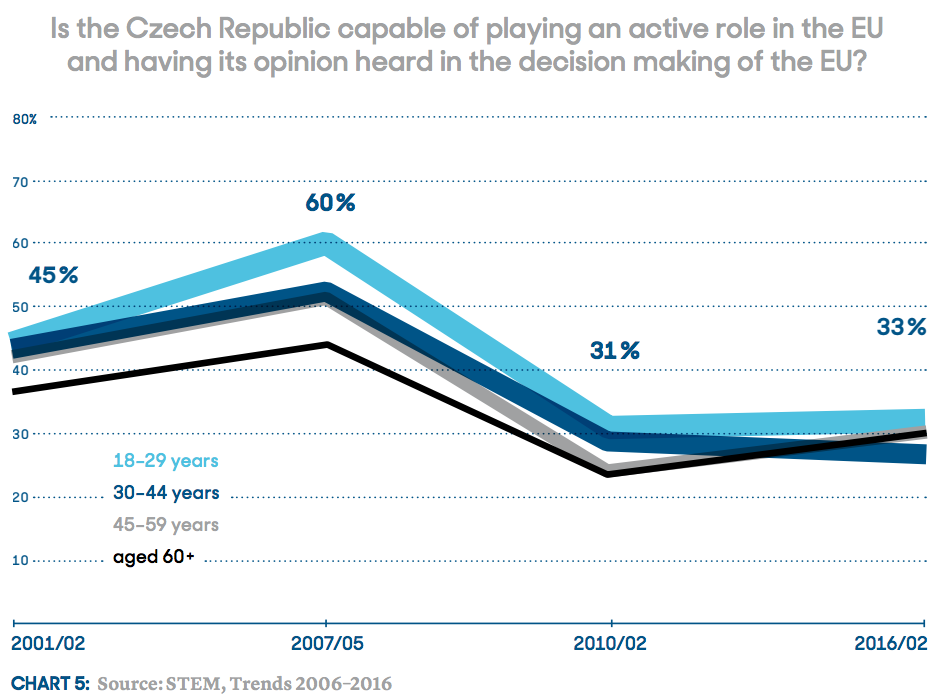

How Do We Rate the Czech Republic’s Active Role in the EU?

In any public debate on the European Union the argument “us” versus “them” tends to crop up quite early on. The view that the European Union is “the others” seems to be quite popular among the Czech public, as if the country could exercise no influence on events and as if, as a member state, it did not have a place at the table where it can champion our interests. Another similar argument is the cliché of “decisions affecting us taken without us” sometimes used in public debates to emphasize a kind of helplessness or powerlessness concerning what we perceive as decisions taken by more powerful countries or institutions.

However, the same issue can also be approached in a positive way, for our research shows that the public expects its elected representatives to play a more proactive role, and that it appreciates it when they insist on exercising this right. The Czech public is willing to support their country in playing a more active role within the European Union.

The curve shows highest ratings among the youngest generation: in February 2009 a full 60 percent were of the opinion that the Czech Republic was capable of playing an active role within the EU and champion its positions in EU decision making.

The generation of senior citizens is at the opposite end of the spectrum, the responses dropping to their lowest level in April 2012 (23%). The following graphic illustrates this development over time:

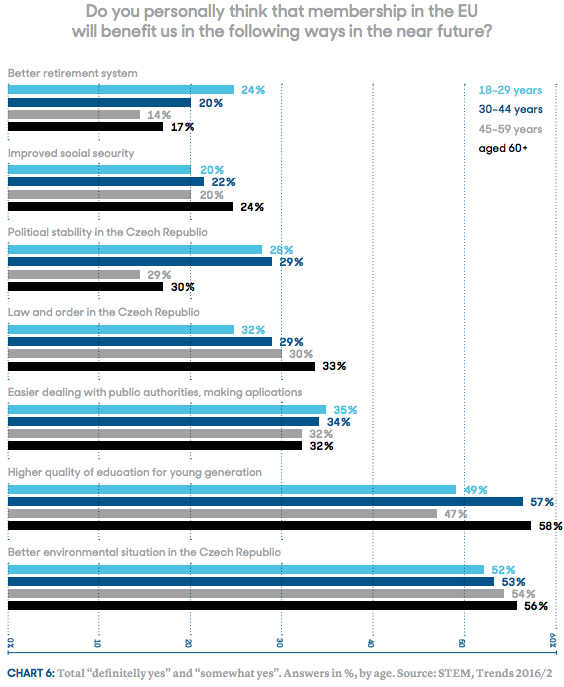

We Expect a Higher Quality of Education

In terms of specific issues in respect of which our country benefits from EU membership, the research has not revealed any statistically significant differences between age groups. Only in terms of expectations of a higher quality of education for the younger generation are the young less optimistic (as are people aged between 45 and 59).

It is also worth noting that when young people consider issues affecting senior citizens (the pension system) they are inclined to view them in a more positive light than the senior citizens themselves. And vice versa: senior citizens tend to have a more positive view of the chances of higher quality education for the younger generation.

Otherwise the results reveal relatively similar attitudes across all age groups. The graphic shows how the public rated selected areas in February 2016.

Trust in Institutions

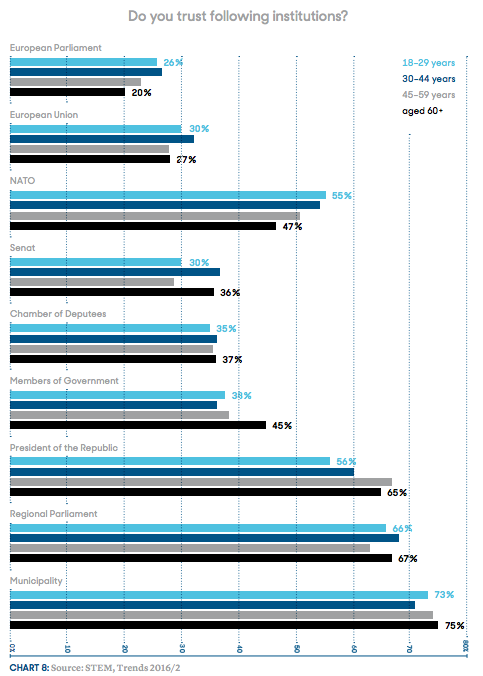

In terms of the degree of public trust in institutions, the data collected in February 2016 examined elected bodies as well as international institutions.

The most trusted institutions are, undoubtedly, the municipal authorities. This is hardly surprising since this finding has been regularly confirmed in consecutive surveys. The degree of trust shown by all age groups in municipal authorities and at town halls level is truly exceptional. The Czech public shows an extremely high level of trust at the level closest to its everyday life.

In this respect the European Parliament is at the opposite end of the spectrum, although it is worth noting that this has not always been the case. The public used to have very high expectations of European integration in general and of the European Parliament in particular. In fact, it had expected European institutions to help improve the country’s administration and used to trust them more than its own government. The dramatic decline in trust occurred later, with the 2016 results showing a record low.

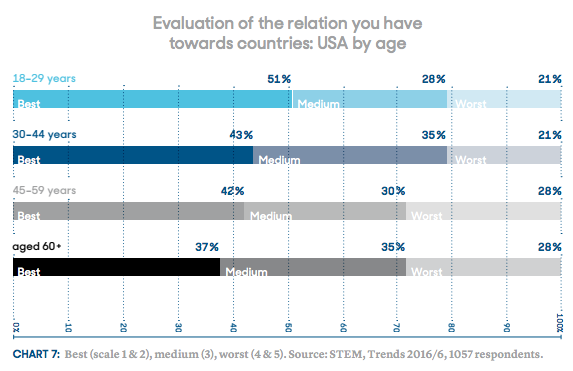

In terms of age the most significant differences regarding the public’s trust in institutions can be observed with regard to three of them. The older age groups tend to show trust in the president and in the individual cabinet members in particular, the youngest generation spontaneously leans towards trusting international institutions such as the EU, the European Parliament, and, particularly, the NATO.

In the case of NATO, the degree of trust among the young is very high (55%). This might be related, among other things, to the fact that people associate NATO with close cooperation with the United States.

In fact, the US as a country is quite unique as far as the Czech public is concerned. When examining attitudes to other countries, the generational effect is much more pronounced in case of the US compared to all other countries. The youngest generation is most open towards the US, as illustrated by the following graphic in which respondents were asked to rank individual countries on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being the best grade. The data was collected in June 2016.

Finally, the last graphic shows the degree of trust in various institutions. Since we are particularly interested in generational differences, the chart deliberately lists both national and international institutions, regardless of whether or not they are elected bodies. The data was collected in 2016.

A Seismograph for Europe?

The long-term data series generated by the STEM Institute and based on regular empirical research represent a unique example of empirical methods applied to the study of society. Our data, collected using the traditional face-to-face method from a representative population sample, goes back to 1990, continuously covering the entire period of political transition as well as the process of integration into European structures.

The selected data presented here demonstrates that following the EU accession, attitudes in Czech society have become somewhat differentiated by age. However, the differences are not significant enough to lose sight of other, more significant, differences. Much greater differences are manifested depending on place of residence, electoral preferences, and especially education level, with university graduates being the most ardent supporters of European integration. In searching for an effective European strategy the Czech Republic might want to consider how to appeal to the less-educated sections of the population.

These seven findings show that the overall support for European integration has been on the slide. This trend is sufficiently pronounced to deserve additional attention not only in analytical terms but first and foremost in terms of concerted political action.

The public is not blind. The people have seen what kind of arguments were instrumental in bringing about the Brexit vote and before being asked to make a similar historic decision they ought to be provided with all of the arguments, be given sufficient time, and be presented with clear priorities in order to reverse this trend. The question is whether there will be time to do so.

Any reversal of the current trend calls not just for enough room for explanations but also for authentic political and opinion leaders capable of making a down-to-earth case for closer European integration in vital areas. What is needed are leaders capable of regaining the trust of all those who are wavering and have doubts. Europe has lived through major upheavals that have shaped our continent. We believe that Czech society, formed by these turning points in history, can play the role of a seismograph.

In this respect, a very clear conclusion is at hand. We have to act because we are faced with major challenges within the wider European context. And when the moment comes to seek calm support and understanding from the public, there might not be a lot of time left to spare.