The divisions within NATO frequently run not between the countries of Eastern and Western Europe but between those who are more willing to respond to immediate needs and those who seem less sensitive to threats, says the former chairman of the NATO Military Committee Petr Pavel, in an interview with Robert Schuster.

ROBERT SCHUSTER: You served as chairman of the NATO Military Committee for three years. How did the international security situation change in this period?

PETR PAVEL: I took up the post shortly after the annexation of Crimea and following heavy fighting in the Donbas region. We viewed the behavior of the Russian Federation at the time as unpredictable and aggressive. We were of the opinion that it represented the height of unpredictability for the security environment. Not only did this environment not improve over the three years, but on the contrary, I feel it was becoming increasingly complicated. And this not just with regard to external protagonists but also to internal ones.

What I have in mind is friction within the Alliance caused by the certain powerful statements that had to be revised and explained later to ensure that the Alliance maintained its greatest strength, i.e. internal cohesion.

Has it been possible to maintain this cohesion over the past few months, given that Russia’s behavior has become even more aggressive?

I prefer not to be too optimistic. I would say that the Alliance is capable of responding effectively by means of a whole range of measures including some that are, strictly speaking, not within its remit, NATO being primarily a military and political organization. Nevertheless, in relation to Russia, some economic and financial instruments have also been deployed in what is partly a reflection of the new character of conflicts in the world and the ways of tackling them. In this respect, it was possible to reach a consensus within the Alliance. On the other hand, a number of more or less controversial issues have emerged, such as the approach to Ukraine.

Specifically, the issue of the sustainability of supporting Ukraine against Russia’s aggression and how the Russian threat is perceived at the moment. When we are repeatedly told that something poses a threat we have, as human beings, the tendency to see it as a normal part of our lives rather than a major threat. Lately, there has been more discussion of China within NATO—until recently the United States was the only country talking about it. The Alliance had not had a specific position in China and had not regarded it as a potential future threat.

Has the Alliance started to focus more on China because of cybersecurity threats?

In the information sphere, in general, we are seeing a new, or more integrated, effect. As the major protagonists realize that military force does not bring about a resolution of conflicts, particularly once a parity in terms of strategic arms has been achieved, they resort to instruments that are more effective in this situation, while also being less costly and capable of being deployed below the threshold of what might be defined as open aggression. This is the case not only with Russia but also with the so-called “Islamic State” and also, to some extent, the Taliban in Afghanistan, and of course also China. All these protagonists make use of opportuni- ties provided by new technology as well as the free sharing of information in Western societies, and they use them to achieve maximum impact.

When, in your view, might NATO be in a position to build a barrier capable of nipping such attempts in the bud?

I think it would be too ambitious to believe that 100% protection of some kind against cyber and information threats can be developed—for that we would have to return to the pre-internet era. On the other hand, both the Alliance and the entire Western community have realized the extent of risk posed by these issues, and a number of decisions to tackle influencing operations of this kind have been made at the level of NATO, the UN, and the European Union, as well as at a national level.

These decisions relate not just to cyber-defense but also to certain types of active measures against these protagonists aimed at disrupting the continuation of their activities. They consist primarily in exposing disinformation, pointing out the sources of fake news, how such fake news is being created and what its intended effects are, to provide ordinary citizens who lack access to the full range of analytical tools with at least a basic idea of what information they can trust and what, by contrast, falls into the category of misleading information.

I think it would be too ambitious to believe that 100% protection of some kind against cyber and information threats can be developed—for that we would have to return to the pre-internet era.

In recent years the tensions arising from Washington’s demands for NATO members states to increase their defense spending have become quite tangible. How much pressure has this put on the functioning of NATO?

The US attempts to push the allies to increase their defense spending and ensure an equal sharing of the burden go back to well before President Donald Trump’s time. It’s just that previous American Presidents had not exerted this pressure so openly. However, regardless of the form it takes, all member states do realize that Washington’s demand is justified and that expenditure must be increased.

There has been quite a strong shift within NATO, not only towards making individual members increase their defense expenditure, but to acknowledge their own weaknesses and explore new areas on which the Alliance had not focused before. This has started happening, with members states gradually increasing their expenditure although this is not meant to be a goal in itself: the point is for the Alliance to acquire specific skills that will provide it with a whole range of strengths it will need to defend itself against any aggressor or threat.

What are the key weaknesses?

Apart from logistics and the ability to ensure mobility across the territory of Europe, which are frequently mentioned, the main weaknesses relate to strategic intelligence, the range of information shared by member states and sharing it in a way that will ensure that everyone has a full picture of the nature of the threat. Then there is the area of cybersecurity, unmanned vehicles, in particular, mentioned earlier.

This year will see 20 years since the NATO accession of the first three countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Have these countries left a mark on the Alliance?

Perhaps surprisingly, the dividing line between countries that are more willing to respond to NATO’s current needs and those who are not, does not run between what used to be Western and Eastern Europe. Some Central and East European countries have approached this issue very responsibly right from the outset. This is particularly the case with the ones directly affected by the threat, such as the Baltic countries and Romania. Then there are countries that are not all that concerned about the threat which, in my view, include the Czech Republic.

If you look at the way the potential threat is being presented in this country, there is much talk of international terrorism and migration, but you rarely hear anything about the threat posed by Russia or China. And when you do, it is presented as something very abstract and remote. A shared understanding and perception of priorities and potential threats is, of course, the basis for the ability to respond to such threats effectively.

Has NATO membership had an impact on public debate in the Czech Republic or elsewhere in Central Europe?

Judging by opinion polls and based on my experience of discussions I have participated in, I must say that only a small majority is convinced that NATO provides us with a security guarantee and that we have benefited from membership. On the other hand, part of our public—influenced by a concerted information campaign on the part of Russia as well as the views of some of our leading politicians—does not regard our membership of NATO as something clearly positive.

Indeed, many believe that we should be more open and pragmatic about our relations with Russia and the non-standard, even aggressive, way Russia has behaved over the past few years. We seem to have a tendency to accept the argument that being a major power, Russia basically has the right to behave as it does even if it violates international principles.

However, right now I have to say that a large part of the Czech public regards our integration into Euro-Atlantic structures as something that has not only contributed to the stability and security of our country but also to its prosperity.

How do the original NATO members view the expansion of the Alliance now? For example, do they not regret the fact that as a result of admitting East European countries, NATO has become Russia’s immediate neighbor?

You can’t expect a homogeneous view on this subject. Some countries certainly do feel some regret about what used to be quite simple patterns of looking at threats at a time when it was obvious who was a friend and who was a foe. This also helped to keep decision-making among twelve, and later sixteen, countries, fairly straightforward which cannot, of course, be compared to a situation where you have 29 members. On the other hand, there are many countries and politicians who see NATO as a guarantor of stability and security in the broader sense. In this respect, they take a positive view of the NATO expansion because of the admission of Central and East European countries has indisputably brought about greater stability in this part of the world.

There has been quite a strong shift within NATO, to acknowledge their own weaknesses and explore new areas on which the Alliance had not focused before.

At the same time, it has forced the new member states to adopt a new culture in their mutual relations and behavior, to look for compromise and not resort to confrontation in dealing with their problems. In this respect the perception is balanced, and I would say that the number of those who see the expansion of NATO as positive definitely surpasses the number of those who think it was a mistake.

A shared understanding and perception of priorities and potential threats is, of course, the basis for the ability to respond to such threats effectively.

Lately, we have seen attempts to get the European Union to strengthen its defense dimension. Wouldn’t this mean competition with NATO? A splitting of forces?

I have always sought to avoid seeing our mutual relations through the optics of the autonomy of a particular organization since organizations tend to jealously guard their own interests. As someone who has been fortunate enough to serve both in the EU and NATO and get to know both organizations from the inside, I think that both organizations are unique in their own way, that both are still relevant in the current environment and that the only way they can resolve current problems effectively is by intensive cooperation. Each organization possesses a unique set of instruments that the other one lacks: they complement one another. It would be pointless if each of them tried to develop the capacities it is lacking if the other one has them, to dupli- cate efforts and compete for their place in the sun. That would be a sure way to hell for the entire community broadly known as the Western democratic world.

NATO’s main strategic document defines three basic tasks: collective defense, crisis resolution and operational security. The last two coincide with the tasks that EU deals with as part of its security and defense policy. So, a certain overlap already exists and mutual coordination is needed to ensure a sensible division of labor instead of rivalry. This doesn’t always happen. Collective defense aside—as that is clearly the domain of NATO and the EU doesn’t have the ambition to develop its capability for collective defense—we are left with crisis resolution and cooperative security.

The only way this can be done is by using not just military but also developmental means. And in this area the European Union is clearly stronger, and not only because it has a much broader portfolio of capabilities than NATO, which is a purely political-military organization. They need to join forces so that the two organizations can jointly resolve crisis situations, particularly in Europe’s immediate neighborhood: NATO, by deploying its extremely effective military means, and the EU, by a combination of military, and particularly developmental and financial tools. Without this, we cannot expect to make progress in dealing with crisis regions in North Africa and the Middle East.

How does NATO manage to maintain a balance between defending its southern flank and the regions in the East?

In terms of the strategic documents which NATO has adopted at its summits in Wales and Warsaw, one of its main tasks is effective deterrence or, failing that, effective defense. The second main task is what in Warsaw was referred to as “projecting stability”, i.e. supporting all measures aimed at alleviating tensions in problem regions and the countries of North Africa and the Middle East.

This will require a balanced effort because, if we focus too much on one area, naturally, problems will accumulate in another area, and vice versa. You can’t divide it up and decide to invest heavily in measures strengthening collective defense now and leave crisis management for later—that is a luxury we can’t afford.

All member states are aware of this, and that is why, in sharing out the tasks between individual countries as part of planning our defense capabilities, NATO is mindful of the full range of threats, so that the states are capable not only of ensuring operational security and crisis management but also of developing the key capabilities needed for collective defense.

How has the functioning of NATO been affected by the emergence of a politician like Donald Trump, who prefers being outspoken to backstage diplomatic negotiations? Has NATO learned to come to terms with this?

The European Union prefers reaching an agreement, that is to say, diplomatic and courteous methods, to open confrontation. This does not preclude engaging in open and controversial debate, but the emphasis is always on gentlemanlike behavior. Donald Trump has brought a kind of spontaneity into our relations that is at odds with the established rules, and this has resulted in some rather tricky moments in negotiations.

However, we have always succeeded in managing the situation in the end, in reaching a deal, even if it sometimes necessitated a pause in the negotiations to enable expert teams to meet behind the scenes and hammer out a compromise solution, as happened at last year’s Brussels summit. Of course, it is a fact of life that these days there are leaders in power, not just in the United States, whose style is different and does not always correspond to what we have been used to. We have to accept this as a fact that ought to help us find new ways of behaving which will succeed in bringing these leaders back and embrace a system that facilitates factual negotiations and results in constructive solutions.

Do you think NATO should expand further, or should the current membership of 29 countries plus Macedonia be final? Georgia, as well as Ukraine, have applied for NATO membership…

NATO has never declared a final limit to its expansion—be it in terms of the number of countries or geographical terms. As long as we see the Alliance as a platform for cooperation, consultation and the seeking of joint solutions, it would be pointless to set such a limit. The question will arise, of course, what contribution potential new members could realistically make to greater stability or, by contrast, if it might provoke a negative reaction that might potentially lead to conflict.

I think all member states are seriously pondering these questions and there is definitively no appetite within the Alliance to expand at any cost. You always have to consider all the pros and cons. The basic precondition for any potential member state is to agree with NATO in terms of its interests as well as the principles it espouses. As long as such an agreement exists, there is also room for negotiation and potential membership.

As for Georgia and Ukraine, these countries were basically given a promise of membership as long ago as in 2008, in Bucharest, when it was stated that these two countries would eventually join NATO. But, of course, no deadline was set because what is more important than a specific date is the meeting of specific criteria. This process is being pursued very intensively with both Ukraine and Georgia: NATO is involved in developing these countries’ military forces to make them compatible with the Alliance in every area of security and defense. The actual NATO membership of these, and perhaps some other, countries, is subject to further negotiation.

Donald Trump has brought a kind of spontaneity into our relations that is at odds with the established rules, and this has resulted in some rather tricky moments in negotiations.

Doesn’t a large number of members reduce the organization’s readiness for action? Doesn’t it make it difficult to find consensus?

It is true that management theory prescribes the optimal number of elements a system ought to have in order to remain manageable and not collapse into chaos. However, I must say that the example of NATO refutes this theory somewhat because all members share the will to find a common solution or a common denominator, and that means that despite partial differences a solution is always found in the end. Over the past three years I have witnessed many complex negotiations when it really looked as if we had reached an impasse and that there was no chance of breaking out of it, but, even if it takes longer, the will to reach agreement always prevails eventually. This is one of the key benefits of being in NATO because it is a genuine community of friends who may not always agree on everything but they know that together their chances of succeeding in a complex world are far greater than if they acted on their own.

Where do you see NATO in ten years’ time?

I would very much like the Alliance to be as unified in ten years’ time as it is now and be able to overcome some problems it is grappling with at the moment. We cannot really expect all the security issues of the world to be resolved in ten years. A factor such as NATO will still be necessary to ensure that the democratic world retains an effective instrument for its own defense and maintains its sovereignty, unencumbered by non-military, or less military, means. So the issue is not so much what I think the situation looks like now but how I would like it to look in order to stay united and be able to resolve the issue of funding, as all member states realize that investing in defense is just as crucial as investing in other areas because the world we live in simply demands it.

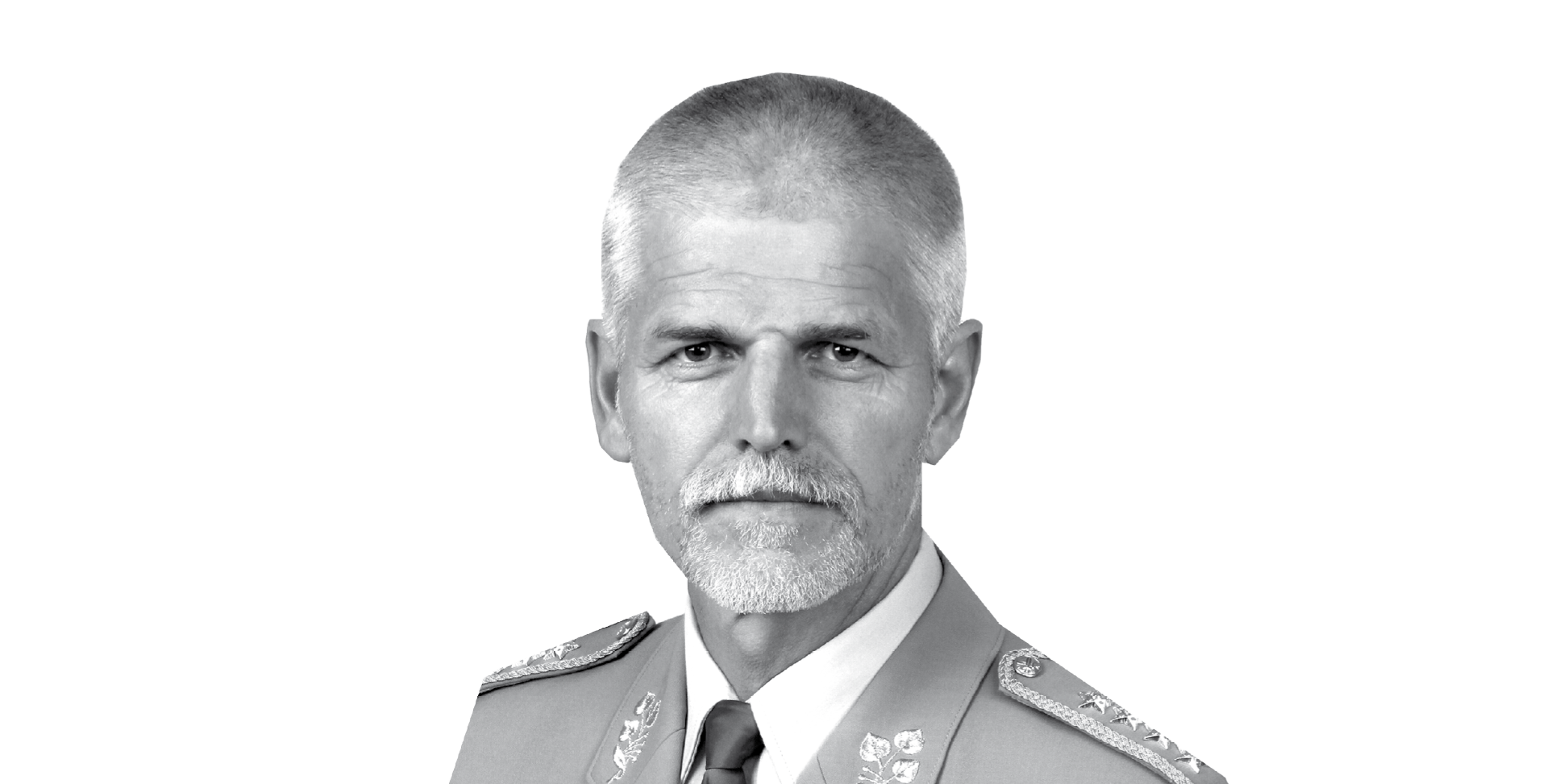

Petr Pavel

(*1961) is a General of the Armed Forces of the Czech Republic. From 2015 to 2018 he served as Chairman of the NATO Military Committee, the first representative of a former Warsaw Pact country to take on the highest military position in the North Atlantic Alliance. From 2012 to 2015 he was Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Czech Republic. He studied at universities in Czechoslovakia/the Czech Republic as well as abroad, including at the Staff College, Camberley, the Royal College of Defense Studies and King’s College London. After graduating, he joined the airborne reconnaissance platoon; in the 1990s he worked for Czech military intelligence and served in UNPROFOR peace missions. His unit was deployed in the rescue of French soldiers trapped in the war zone between the Serbs and Croats. From 2002 to 2007 he served, successively, as Commander of Special Forces, Deputy Joint Forces Commander, Deputy Director of the Operations Division at the Ministry of Defense, and Deputy Chief of the General Staff.