The initial recovery phase after the global financial crisis and the eurozone crisis was marked by a remarkable lack of new policy ideas. There is no need to repeat this experience. The current crisis is an opportunity to put the new policy ideas, that have come out of these debates, into practice.

When the world economy was hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, the eurozone economy had not yet fully recovered from the previous crises. This was in part due to a wrongheaded insistence on fiscal austerity. Over a decade after the global financial crisis in 2008, unemployment rates in most southern eurozone countries remained significantly above their pre-crisis levels. Fiscal consolidation efforts contributed to this slow recovery and with the current economic crisis being certain to lead to a sharp increase in public debt levels, it is vitally important that Europe does not regress into austerity again. Beyond that, the current situation is also an opportunity to look at and implement new economic ideas, particularly when it comes to fiscal policy.

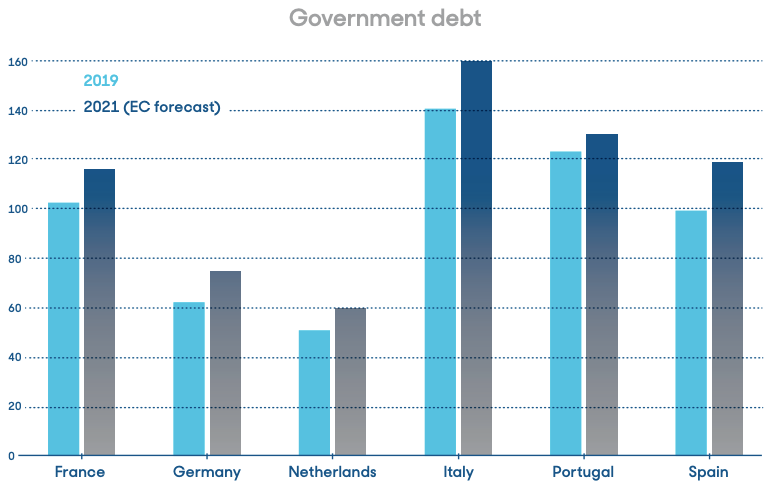

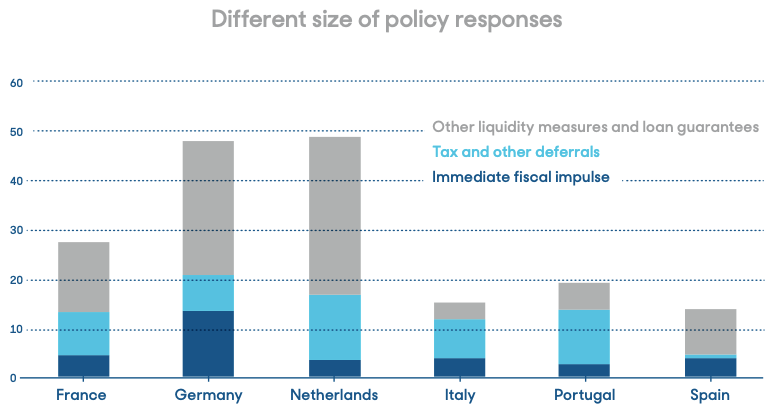

In order to be able to put large parts of their economies into something like hibernation, which was required to enable the lockdowns necessary to fight the virus, governments turned on the fiscal taps. Large-scale furlough schemes, designed to ensure linkages between employers and employees, together with support for businesses through grants and loan guarantees will, together with plummeting tax revenue, lead to unprecedented budget deficits. The different size of various governments’ rescue packages already highlights that some countries are better placed to absorb the resulting increase in government debt.

The exact economic impact of the current crisis on different economies remains unknown. In its spring economic forecasts, which should be read with even more caution than normal economic forecast, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects the eurozone economy as a whole to contract by 10.2%.

Economic Divergence in Europe

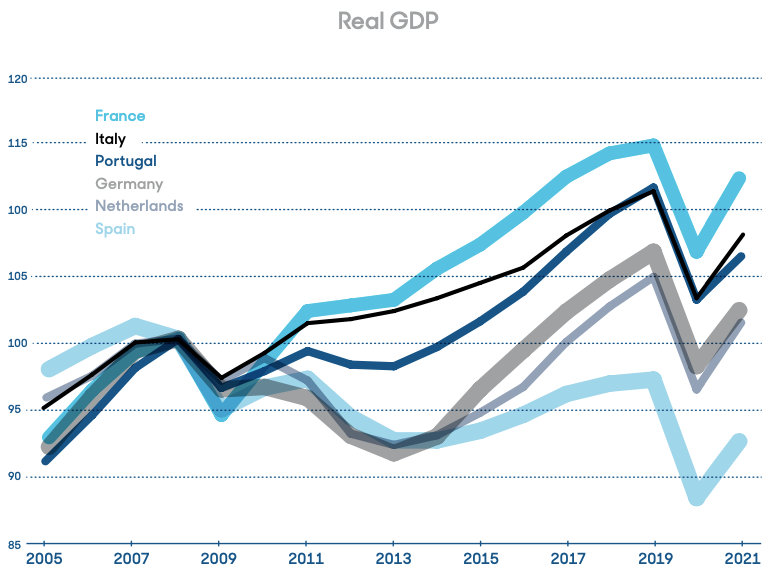

The exact economic impact of the current crisis on different economies remains unknown. In its spring economic forecasts, which should be read with even more caution than normal economic forecasts due to the uncertainty created by the course of the health crisis and the fact that the economic disruption is unprecedented and thus probably not well captured by any economic models, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects the eurozone economy as a whole to contract by 10.2%. By comparison, the global financial crisis in 2009 led to a contraction of 4.5%. The European Commission expects the unemployment rate to increase from 7.5% last year to 9.6% this year and the modest average government budget deficit of 0.6% of GDP last year to increase to 8.5%. Behind these headline numbers, there is significant variation between countries.

CHART 1: in % of GDP

CHART 2: 2008 = 100

CHART 3: in % of 2019 GDP

Countries such as Germany and the Netherlands went into a crisis with low and falling debt levels due to several years of budget surpluses. Meanwhile, the southern euro member states went into it still running budget deficits and with high debt levels, in the case of Italy at 135% of GDP. These economies are also likely to be harder hit, as they were among the hotspots for the virus in Europe and thus locked down earlier and more severely. On top of that, the latter’s reliance on industries such as tourism, which are much less likely to be able to adapt than the industry and business services dominant in many northern economies, means they are likely to suffer economic disruption longer. The IMF expects the German and Dutch economies to contract by 7.8% and 7.7% respectively this year, while it foresees the Italian and Spanish economies contracting by 12.8%. As a result, the Spanish and Italian economies would still be just over 7% smaller in 2021 than in 2019, while output in German and the Netherlands would be only about 3% lower.

In 2009, the Chinese government engaged in massive stimulus, which helped to quickly turn around its economy and contributed to a rapid recovery in Germany. A repetition of this scenario is unlikely.

The difference in fiscal space to respond to the crisis is visible when looking at the size of the rescue packages. Whereas the German government has announced direct fiscal measures worth just over 13% of 2019 GDP, according to the think tank Bruegel, the packages announced by Italy and Spain are both worth only around 3.5% of GDP. This creates the risk of even further divergence in economic fortunes between the northern and southern member states as a result of this crisis.

The €750bn recovery fund agreed by the European Council, including €390bn in subsidies for member states hardest hit by the pandemic, would contain some redistribution and help to limit divergence. But it is too small, its spending spread too thinly across the continent and too slow to avert significant economic divergence within the bloc. For example, Italy can expect a fiscal boost from it of only about 1% of GDP per year in the next two years. While this will be helpful, given the size of the economic contraction, it is highly unlikely to be anywhere near enough to significantly boost the recovery.

After the Immediate Crisis

Beyond the emergency measures already put in place by governments, there is not much they can do to stimulate demand when economies are still in full or partial lockdown. Economies will not, however, immediately bounce back. Despite the ostensibly successful hibernation, many companies are likely to go or have gone out of business and the true extent of the unemployment caused by the crisis is likely to have been obscured by the furlough schemes. This argues in favour of sustained economic stimulus after the initial phase of the crisis.

The global nature of the current crisis further strengthens the case for sustained fiscal stimulus in the recovery phase. In 2009, the Chinese government engaged in massive stimulus, which helped to quickly turn around its economy and contributed to a rapid recovery in Germany. A repetition of this scenario is unlikely as China is itself running up against a maximum by which it can reduce domestic debt, which played a large role in the previous Chinese stimulus efforts. Europe will thus not be able to rely on foreign demand for its recovery, as it did during the recovery from the eurozone crisis. This might go some way to explaining why the German government, which quickly retreated from fiscal stimulus during the previous crisis, seems to now be willing to turn on the fiscal taps.

The experience following the previous crisis showed that a premature turn to fiscal consolidation lengthens the recovery, and through that probably makes it harder to achieve headline budget goals in the medium term.

The Commission let go of the fiscal rules for this year, as the rules enable it to do in emergencies, but there is no guarantee that there will not be a return to a singular focus on headline budget numbers. The experience following the previous crisis showed that a premature turn to fiscal consolidation lengthens the recovery, and through that probably makes it harder to achieve headline budget goals in the medium term. Encouragingly, several governments have already suggested that they agree with this analysis, including the previously hawkish Dutch and German finance ministers.

The headline deficits generated by the current crisis will undoubtedly lead some commentators, however, to revert to calls for governments to ‘tighten their belts’. This would be particularly problematic for the southern economies. European policymakers should be particularly careful with pushing for more austerity as another economic experience, like that of the post-euro crisis era, runs the risk of tipping several electorates, most notably the Italian, towards full-blown Euroscepticism.

What to Do

Support from the European Central Bank (ECB) should and probably will remain forthcoming. The ECB has thus far played its role in creating the necessary fiscal space for eurozone governments. Its interventions to support the financial system have helped avoid the economic crisis turning into a financial crisis. By announcing, and subsequently enlarging, a bond-buying program, the so-called Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) the ECB ensured that countries such as Italy and Spain would not be kept from doing the necessary spending by rising government bond yields.

The under-lying drivers of the low-interest-rate environment, including demographic factors and the lack of inflation, will also remain in place, leaving space open for the ECB. There is room for monetary policy to play an enlarged role. It could, for instance, incentivise certain types of investment through dual interest rates. There is only so much it can do though. Europe’s monetary policymakers have been calling for years for fiscal authorities to carry more of the burden and this will be even more necessary in the coming years than before the age of corona.

Firstly, it is important that policymakers allow regular automatic stabilizers to do their work and only retreat the special crisis measures gradually. The increase in unemployment should not be met with a decrease in unemployment benefits in the hope that, in times of suppressed demand, this could incentive people to go back to work. Secondly, they should look at traditional stimulus measures, including through increasing investment in areas such as infrastructure and education. Public investment was among the areas on which governments cut back most in the previous crisis, harming the long-run growth potential of their economies.

Public investment was among the areas on which governments cut back most in the previous crisis, harming the long-run growth potential of their economies.

The European recovery fund will finance some of this, but this will not be enough. Thirdly, policymakers should not let this crisis go to waste and use this opportunity to engage with some of the many ideas lying around that have the potential to not just boost the economy but also diminish the attractiveness of populist alternatives. Populist opposition parties have generally had a bad crisis, with voters rallying around governing parties according to polls across large parts of the continent. There is nothing to say this will last, however, adding even more urgency to the need for new policy solutions, ones that will also help address the discontent driving much of the populist anger.

Exploring New Policy Ideas

The initial recovery phase after the global financial crisis and the eurozone crisis was marked by a remarkable lack of new policy ideas. Public anger, with the political, economic and financial establishment that oversaw the greatest economic collapse since the Great Depression, found its outlet in protest movements like Occupy Wall Street, the Indignados in Spain and a boost for right-wing populism across the western world. These often turned out to be, however, empty movements when it came to new ideas and a positive vision of where to go. There is no need to repeat this experience. For instance, the work of people like Thomas Piketty has put the spotlight on inequality and has changed the debate around the economic and fiscal policy. The current crisis is an opportunity to put the new policy ideas, that have come out of these debates, into practice.

One of the most exciting is to combine the fight against inequality with direct transfers to households, sometimes referred to as helicopter money. This could even be combined with other measures, such as carbon taxes.

Some countries have been experimenting with direct payments to households during the crisis. Most notably, this US government paid $1200 to households but Spain has also set up a guaranteed minimum income for poorer households. Instituting direct transfers to households or even a universal basic income can be done in several ways. One of the most exciting is to combine the fight against inequality with direct transfers to households, sometimes referred to as helicopter money. This could even be combined with other measures, such as carbon taxes that would be fed back to households as direct transfers, a so-called carbon dividend.

During the previous crisis, it was often funding for local public services that were cut the most. We know that those areas most affected by decreases in service levels due to austerity are more vulnerable to populist movements. Furthermore, the current crisis has shown the value of well-functioning local public services as they have played a large role in containing the virus in those countries most successful at doing so, including through their contributions to testing and tracing schemes.

Governments should not just rethink the spending side though; new forms of taxation should also be considered. Many governments have already announced or are considering temporary cuts in value-added taxes. While this is positive from a redistribution perspective, it would be preferable to look at more durable ways of shifting the tax burden onto those more able to carry it. In other words, shifting the burden of taxation further away from the poor to the rich and shifting it away from labor income towards capital income. In other words, it is time to start experimenting with wealth taxes and more efficient corporate taxes.

These measures merely scratch the surface of what is possible and what has been put on the table in recent years. Innovative solutions might also be needed to deal with the large debt stocks resulting from the crisis, including possibly explicit debt monetization. Having seen the power of the state at work in an efficient and effective manner, the current situation provides an ideal opportunity to build political support for a model based on a larger role for the state in Europe in managing aggregate demand. This will be even more important in the countries hardest hit by the crisis and most at risk of drifting away from the European project and good government.