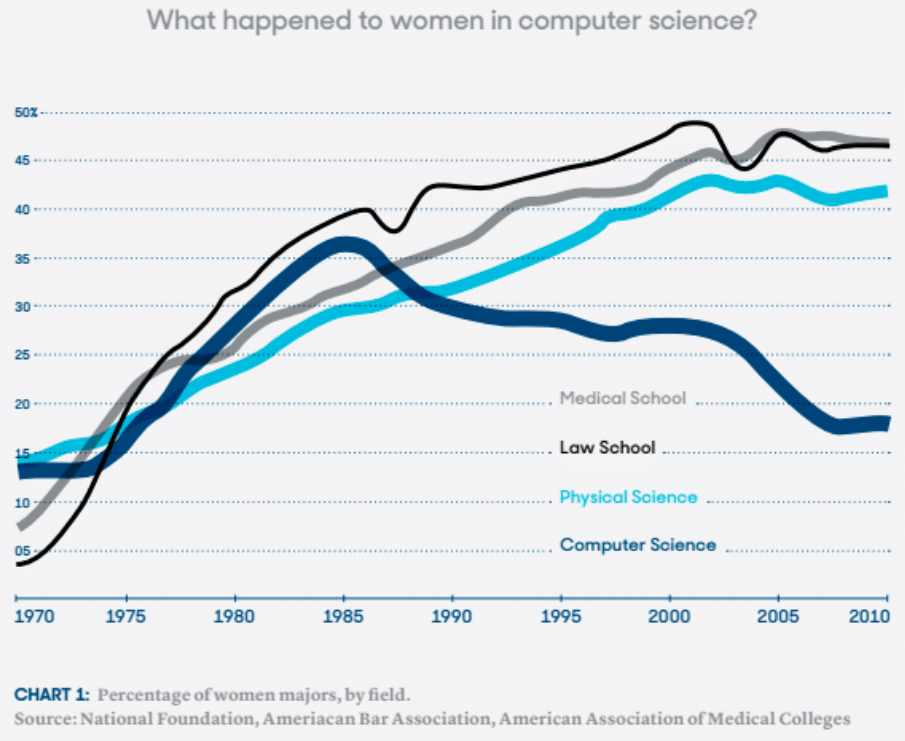

Women in IT, or rather, those missing from IT, have recently been at the center of global debate. Women find it difficult to break through the glass ceiling in politics and business, and since the 1980s their share in male-dominated fields such as information technology has actually been decreasing.

Debate has focused on the need to appeal to and cultivate new talent currently missing from IT, on the potential benefits of gender-diverse teams for increasing companies’ competitiveness, as well as on the urgent need to increase digital literacy among the population as a whole. Those who appreciate the positive contribution women have made to information technology are examining the reasons why there are so few of them in the sector in order to identify the obstacles that may be preventing women from being involved in IT and to find ways of motivating women to seek training and careers in the sector.

Empirical studies carried out at Stanford University demonstrate that gender-diverse teams perform better in the long-term compared with single gender teams, and consistently generate better ideas.

Why Do We Need Women in IT?

Top managers in most companies, national and supranational institutions, and society as a whole agree on the vital need to empower women in top positions as well as in sectors where they are badly needed but currently constitute a minority.

— Women in business represent new potential for innovation since they bring a fresh perspective to problem-solving, product design, and user-friendliness. Empirical studies carried out at Stanford University demonstrate that gender-diverse teams perform better in the long-term compared with single gender teams, and consistently generate better ideas.1

— Moreover, statistics from Deloitte2 show that, on average, women make 85% of all purchasing decisions, and use apps3 more frequently than men. In terms of increased competitiveness it thus makes sense to involve women from the early stage of product development.

Despite the fact that the first programmers were female, the female to male ratio in IT has declined rapidly since 1984 when personal computers became household items.

— In fact, a European Commission study4 has estimated the effect of greater involvement of women in the digital economy within the European Union in terms of GDP growth at 9 million EUR.

— There is increasingly widespread recognition of the fact that loyalty is a characteristic female trait, and therefore attracting female staff can reduce turnover and foster longer-term employer-employee relations.

— Women are regarded as having more empathy and being more communicative, which results in stereotyping both women and men in the education process. In team work, in turn, this results in a more seamless working environment.

— Last but not least, women represent a fresh source of new talent that is desperately needed in the IT labor market. The latest data show that the Czech Republic is currently short of over 30,000 IT specialists, forcing employers to recruit candidates from abroad and raising awareness that women constitute a huge source of new labor.

Why Are There No Women in IT (Yet)?

Despite the fact that the first programmers were female5 and that in the 1980s women comprised over 35% of computer science students, the female to male ratio in IT has declined rapidly since 1984 when personal computers became household items.

Nowadays there are 29 women6 for every 1,000 graduates with IT-related degrees, and only four of them work in programming. The main reason for this decrease is the way personal computers have been marketed. Like all toys, they were targeted at a single gender, with boys initially being the ones supposed to play with computers. TV adverts created the typical profile of an IT specialist, with the image of a nerd as the dominant stereotype in people’s minds. As a logical consequence of this image, women fail to identify with this role and tend to aspire to other professions after completing their secondary education.

What Is the Society’s Response to the Lack of Women in IT and Why Is It Inadequate?

Over the past decade, there has been a decline in interest in IT education and training and employment among women. There have been many attempts to identify the obstacles to women’s entry into IT and several ways of removing them have been proposed. Attempts have been made to motivate women to aspire to an education and career in the sector, using both soft instruments such as public discussions aimed at changing the stereotypical view of women as well harder measures like the introduction of quotas and affirmative action favoring women in job interviews and support programs.

The enforcement of gender diversity breeds anxiety and the discussions in the Western world have turned into a game of political correctness.

Although many of these actions are well-intentioned, they often produce rather unfortunate results. The enforcement of gender diversity breeds anxiety and the discussions in the Western world have turned into a game of political correctness. The purpose of positive discrimination is to create opportunities for a particular group that would not be able to access them under normal circumstances. Admittedly, anyone—be they male or female—has equal access to an IT education or choice of career. However, women tend to make less use of these opportunities because of deep-seated prejudices, stereotyping, and barriers of their own making. On the other hand, affirmative action has some negative impacts, too. It is an extremely delicate tool that must be used properly. It is justified, provided that it is seen as a short-term measure that aims to disrupt the routine of the single-sex cycle. In the long run, however, internal company programs targeting only women, quotas, and the privileging of female candidates in job interviews are unfair artificial constructs. They are harmful to women already employed by a company7 and can result in attracting a pool of weaker candidates. Ultimately, these are merely one-off policies that do nothing to change women’s internal motivation, overcome the barriers preventing them from entering the sector, and they are mystifying IT and IT specialists.

Why Is Education the Only Possible Answer?

First of all, we have to be clear about what must be the focus of social change. All the policies listed above are responses to a structural inequality and they raise questions about the issue. That is a good thing. However, the question that really needs asking is not “Why do we need women in IT?” but rather “Why do women need IT?” Technological growth affects the way we live, communicate, and work. Over the coming decades, up to 60% of existing jobs will be lost to automation; indeed, even today the demands for a minimum of basic computer literacy in nearly all jobs are on the rise and becoming a necessity. Women working at post office counters, in marketing departments, and social services will have no option but to retrain. Women cannot afford to remain on the sidelines. And they should not want to, either. IT offers creative, highly flexible, and financially attractive work with long-term career prospects.

The question that really needs asking is not “Why do we need women in IT?” but rather “Why do women need IT?”

This is precisely the reason Czechitas, an organization that educates women and inspires them to seek IT careers, was established in 2014. It strives to demonstrate that IT is an interesting area of work that need not necessarily be difficult nor, more importantly, be limited to one gender. Initially established to provide female students in Brno with an opportunity to try their hand at programming, it now aims to achieve major social change. The first weekend courses for working women aged 20 to 40 already showed that the concept of teaching IT skills targeting a single group, i.e. women, brings fruit. We created an environment in which women were not afraid to ask seemingly trivial questions, where women programmers were regarded as normal, indeed attractive, and where women had opportunities to design web pages and to discover that it is not as hard as they had imagined. We have removed the barrier of the fear of failure, demystified IT, and disproved false notions about the IT environment being limited to one gender. We have equipped women with the tools to enable them to pursue further education, and within a year or two we have trained brand-new candidates for IT jobs who have come from completely different fields. We have created stories of women who have regained their confidence after maternity leave, using their newly-gained qualifications to apply for part-time jobs in IT. We can share stories of women with degrees in social studies, who had worked as hair-dressers or as personal assistants to company directors, and who have been spurred by our course and their own studies into IT developer jobs. We have stories of women who had worked with tables in MS Word in marketing departments but now use data analytics and can reformat newsletter templates in HTML in their new jobs. Stories of women who have created their own webpages and have launched their own businesses using their new-found self-confidence. And stories of young women who, after leaving secondary school, have gone on to study IT to degree level.

How Was It Perceived in the Male-Dominated World?

In the four years of our existence we have come a long way, learning a great deal about education, women’s motivations, and about ourselves. Our first programming courses were community-based. Many volunteers and IT specialists who are still committed to our shared vision have devoted their weekends to teaching women and children. What has surprised us was the hugely positive perception of our activities in the male-dominated world. Sharing skills, which is common in technical communities, has generated great motivation and social impact in educating women who are new to IT.

It has been clear from the start that there was a huge potential for growth in terms of themes, forms, location, and target groups for our courses, and many companies have understood the potential of new talent and have shown interest in the women who have graduated from our courses. In 2015, we received the Social Impact Award and started to focus more on the long-term sustainability of our endeavor and on the independence of Czechitas. We have widened our portfolio of courses to include a whole range of technologies and IT areas and, jointly with Keboola, have developed data analytics courses, which are now in the public domain and are being organized in Asia, USA, Great Britain, Australia, and Africa. We have also realized that thinking about choosing a future profession should begin at an earlier age. That is why we have launched our Programming Academy project, which trains teachers and children in primary and secondary schools. We are introducing teachers to programming curricula for after-school clubs. After attending our summer school, a week-long camp where they could discover what IT is and what it is not, many girls who had previously not known what they wanted to study opted for IT. An admirable 80% of the participants have chosen IT-focused university degrees. Our endeavors have also been noted abroad. Our educational activities abroad have been supported by a German company which has also helped us set up local branches through the #czechitasgoglobal project. Our work has been recognized by the European Union awarding us the European Citizen Prize in 2016, and were the first organization in East-Central Europe that Google.org has given a grant to develop a Digital Academy, our first retraining course for women. We are known as far away as the other side of the Atlantic: in Texas in 2017 we received the SXSW Community Service Award.

An explanation for the insufficient interest in IT jobs among women is the stereotyping and mystifying of the sector.

What Have We Learned?

At the time of writing (late 2017), we are running 150 training seminars a year, 7,000 women have graduated from our courses with hundreds of them having already gained—and thousands coming close to gaining—new or better IT jobs. Czechitas now represents an educational ecosystem that involves a variety of forms of alternative education, from workshops, evening courses, hands-on work on real-life projects, lectures, to mentoring, internships in companies, online courses, as well as community study groups. There is a whole range of biological, structural, and socio-cultural reasons why women pursue a variety of career choices and, as a result, do not end up in IT. An explanation for the insufficient interest in IT jobs among women is the stereotyping and mystifying of the sector, the image of IT-professionals created by marketing, as well as a lack of self-confidence and information with regard to IT. It turns out that the mold of the stereotype can be broken by showing inspirational examples of women in IT and by training that overcomes knowledge barriers. Our study Women in IT8 has revealed that women are often put off IT by the way they are brought up and educated, mostly by men.

Are We on the Threshold of an Ideal World?

Providing services such as education to a limited group of people does not constitute positive discrimination. All it does is make it possible to adjust the environment to a particular target group so that it can deliver demonstrably better results than the existing systems. After some time, once a woman has acquired the necessary skills to work as junior IT specialist, she can enter the labor market, empowered to compete with men in fair competition: without prejudice but also without any allowances having to be made, based only on the skills, knowledge, cultural fit, and values each individual can offer.

On our journey we have also become aware of the obstacles that remain: (1) impatient companies that expect an immediate supply of new talent and are not willing to invest time, energy, and money into training and educating new people; (2) prejudice vis-à-vis IT specialists, women in the IT sector in general; and, last but not least, (3) independence and sustainability of our non-profit, community based but financially self-sufficient organization. Nevertheless, these are not insurmountable obstacles. These are challenges that make our struggle for a growing number of women in IT even more exciting. We look forward to many more success stories.

We invite the alumni of Aspen Young Leader Programme to present their projects, thoughts and inspiration in Aspen Review. Aspn.me/AYLP

1. http://snap.stanford.edu/class/cs224w-readings/burt00capital.pdf

2. https://dupress.deloitte.com/dup-us-en/deloitte-review/issue-8/diversity-as-an-engine-of-innovation.html

3. http://www.parksassociates.com/blog/article/parks-pr2012-cdp-women

4. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/bringing-more-women-eu-digital-sector-would-bring-€9-billion-annual-gdp-boost

5. As early as in the 19th century, Ada Lovelace wrote an algorithm for a computer (that did not exist at the time). The first computer “bug” and compiler was also invented by a woman—Grace Hopper—as early as 1945. One year later, six women did the programming on the first electronic computer, ENIAC.

6. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/bringing-more-women-eu-digital-sector-would-bring-€9-billion-annual-gdp-boost

7. This is known as the Queen Bee Effect – women who have reached a position of authority through their own efforts defend their territory, but then find have to defend their status vis a vis their femaile subordinates.

8. https://www.czechitas.cz/cs/blog