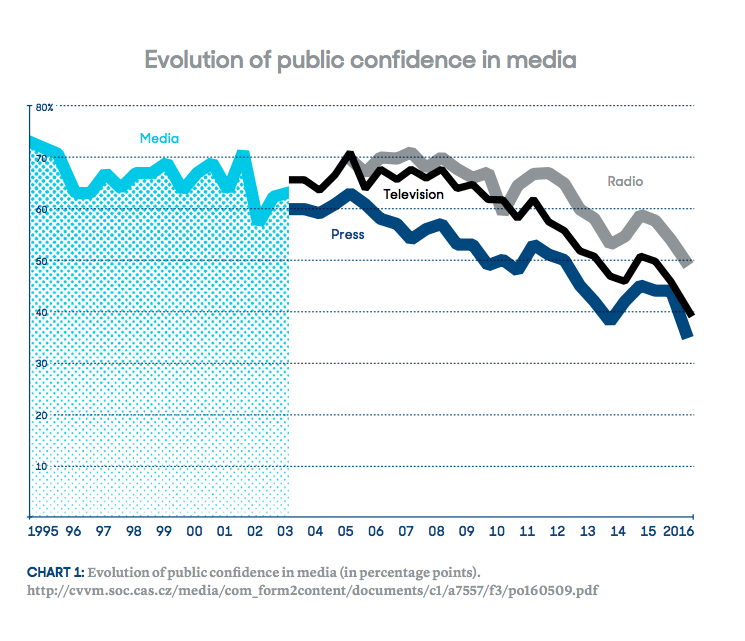

Since 1995, when the Centre for the Study of Public Opinion found that 70% of the respondents trusted Czech media, the Czech Republic has seen a gradual decline in this trust. In an interesting parallel development, public trust in politics has also been declining since 2010. In April 2016 the print media enjoyed the trust of a mere 36% of the public. Apart from the fact that media are a reflection of public opinion and politics—any trust they enjoy necessarily being but a function of political and economic crises or global events at large—some politicians sense that media are an easy target.

All you need to control the media is a smattering of marketing skills and a familiarity with Big Data and lo and behold—a picture of a new type of politics emerges. It is politics for the present-day era, quite different from the interwar period when statesmen of Thomas G. Masaryk’s stature were at the helm.

Rather than politicians, the new politics is controlled by their spin doctors. In this kind of politics the recipient’s opinion carries more weight than a politician’s view.

In this type of politics the politician himself becomes the medium, i.e. a reflection of his electorate, rather than a trustworthy leader with strong views.

Is Post-Factual Era a Real Phenomenon?

Our society is often described as post-factual, indeed in 2016 the Oxford Dictionary picked the word “post-truth” as its word of the year. In some respects, Trump’s election as US president, Brexit, the rise of populist and extremist parties in Europe, as well as the intensifying disinformation campaign from the East (often uncritically accepted by the public) might suggest that we live in an era where facts no longer matter.

This may well be true, except that it is not exactly new. After all, this is not the first time that someone has tried to present information that is not truthful or fact-based, whether we look at the past century when totalitarian regimes rose to power in parts of Europe, or at the period just before the end of communism, or recall the notorious speech by Ronald Reagan from thirty years ago, in which he apologized for having misled the public regarding the Iran Contra case, saying:

My heart and my best intentions still tell me that it’s true, but the facts and the evidence tell me it is not.

–Ronald Reagan

The label “post-factual” may well apply to the way certain political figures or prevailing opinion presented historical events at various stages of human societies. The fact remains that in the era of expanding digital media and social networks, opinions are mediated in a different way—be they facts, emotions, or other output generated by spin doctors, i.e. the kind of marketers and sociologists like Michal Kosinski, whose skillful use of Big Data is said to have contributed to Donald Trump’s victory.

I’m the owner and I’m a politician

Furthermore, the marketization of politics has created a completely new environment in which media and media conglomerates operate. The minute politicians turn into media owners, they face a glaring conflict of interest. This also puts media consumers and journalists in a difficult position, ultimately affecting the transparency of the democratic system or even undermining it. The big question is whether, in cases like this, self-regulation can work. A study of the coverage of the most recent regional and senate elections in the Czech Republic by the daily press and some online media has shown that it is not at all a straightforward matter. At certain points the same media that appeared to present neutral information have shown uncritical bias towards their owner.

Nor must we forget the situation in Poland, Hungary, and other countries where public media have become the target of political attacks. Lately, this dangerous endeavor to control the media has been, to some extent, counterbalanced by a number of emerging smaller and independent media projects across the Visegrad region. The question remains whether this model is economically viable in the long run and, more importantly, whether we should be willing to put up with this state of affairs, as this would mean damaging the general confidence in the media, their transparency, and, ultimately, also their mission. This particularly affects some social groups that are not always capable of critically assessing the situation, such as the elderly, those who are less educated and live on smaller incomes, and children.

Young People as Feedback in Functioning Society

These days children are growing up in an online environment, their smartphones (the prefix smart may soon be redundant) virtually part of their hands. Teenagers in Europe and the US tend to spend between 3.5 and 9 hours a day online and consuming media, accessing social networks up to 100 times a day. [5,6] Paradoxically, only a negligible number of teachers focus on digital media as part of primary education. This situation exposes the dismal state of the entire education system as it fails to adequately prepare for life individuals that will reach their productive age within 10 to 20 years, i.e. at a time when they are likely to change jobs two or three times in their lifetime. Similarly, the education system fails to provide deeper insights into issues relating to present-day media, including the internet and social networks.

The Mediated Reality

This in spite of the fact that it was the young generation that spearheaded the age of YouTube and the bedroom culture phenomenon. Only few people born before 1990 can relate to these innovations, as they reflect very different values, technological processes, and perhaps a different lifestyle: a world experienced by a child or a teenager via their mobile phone or a computer in his or her own bedroom.

Children’s attempts to escape the supervision of their parents, who are scared to let them out of the house on their own, coupled with the need to spend time with their peers and compounded by the evolution of digital technologies have created a new media environment which starts in children’s bedrooms.

This is what has spawned the most popular YouTube channels and resulted in young people being constantly plugged into social networks. Bedroom culture is presented as the very opposite of TV culture, when entire families used to gather to watch sitcoms such as Step by Step. The young people of today experience the mediated world in a completely different way.

Bedroom Culture as Engine Generating New World

Children and young adults often believe their experiences in a mediated environment to be reality. In recent years this kind of experience has become increasingly frequent due to social networks and media development in general and the development of modern technologies in particular. Their recipients lack the experience to read critically or within a wider context. It is difficult, indeed impossible, to navigate this environment without reference points provided by basic education. Yet this kind of perception of reality has had a profound impact on our society. We are locked within a world of mediated reality, in its social construct, and, we, in turn, increase its impact. All this helps to drive the cycle and resets social norms.

Living in a Social Media Bubble

This kind of society is much more conducive to disinformation, populism, rash reactions, and simplifications of every kind, as well as the uncritical reception of news and other manifestations of oligarchic tendencies of media owners. The best antidote is an understanding of the context, which enables us to trust media based on an awareness of their ownership relations and other affiliations, and to assess the information they provide based on this information. To ensure this, we need not just education about the context but also media education, in the sense of understanding the environment and the way information is being used. And this kind of education, in turn, affects the overall confidence in the media as an institution.

If we accept that media organizations have to observe certain rules and regulations in order to be allowed to publish newspapers, we must necessarily also accept that social media—or rather, their owners and publishers—have to be subject to similar rules, too.

Self-regulation can function only as long as we do not create an artificial system that selects on our behalf the content that we should see. Facebook sorts the content and selects what information it deems to be most relevant for us; it is most frequently compared with Twitter, which, in this respect, really is merely a platform for transmitting news.

The Echo Chamber Life

It is the sorting and selecting that generates profits and enhances the engagement with a particular social network while, at the same time, lacking transparency and greatly contributing to the creation of the echo chambers and bubbles that we live in. As a result, if an election is coming up, we feel that all our friends will vote for the political party that we support: in the case of Brexit we all have a clear preference for one particular future for the UK and Europe, in the case of the US presidential election it is just as obvious to us as to all our Facebook friends who to vote for and who to support.

As if it was not hard enough to escape our bubbles and confront our views with those of others, all of a sudden we are finding ourselves in an environment which, in itself, is merely virtual reality. And without understanding how this mechanism works we cannot possibly consume Facebook as a medium in a responsible way, i.e. we cannot read the information it feeds us within a context, prevent it entrenching a mediated reality in which we blindly trust. Even if this or that social network may signal a breakthrough in the history of communication, like most other media it primarily serves the economic interests of its owners, which may quite conceivably include powerful political interests.

China Buying Facebook? Public Social Network!

Such a situation could arise quite easily. A Chinese investor bent on acquiring a media publisher in the Czech Republic could simply direct their investment to the online environment. Just like certain media owned by a particular publishing house that reported on the Dalai Lama’s visit in the Czech Republic in a distorted way, the owner of a social network could simply misuse the online environment in a similar manner. This environment is currently, in some respects, more difficult to monitor than press or TV, because a specific part of its content is displayed only to specific groups of users, based on thoroughly researched and constantly evolving algorithms. Facebook is already practicing this kind of selection although it is probably more interested in increasing its advertising sales than fighting the Dalai Lama.

It is also conceivable that someone will suggest that social networks should have the status of public service providers, along with radio and television. Indeed, they could become a multinational, say pan-European or transatlantic entity, known as WWSN – World Wide Social Network. Fans of Orwell, Watergate, or anyone familiar with the current Polish public media landscape can probably envision a script to provide material for a feature film—a three-parter at the very least.

Paradox of Our Times: I Distrust, yet I Read

In terms of media credibility it is our interpretation that is as fundamental as ever, for it is

the only way of ensuring that whoever owns the information, and whatever spin is put on it, we will be able to identify it and critically assess it. And this is where media education can play a crucial role.

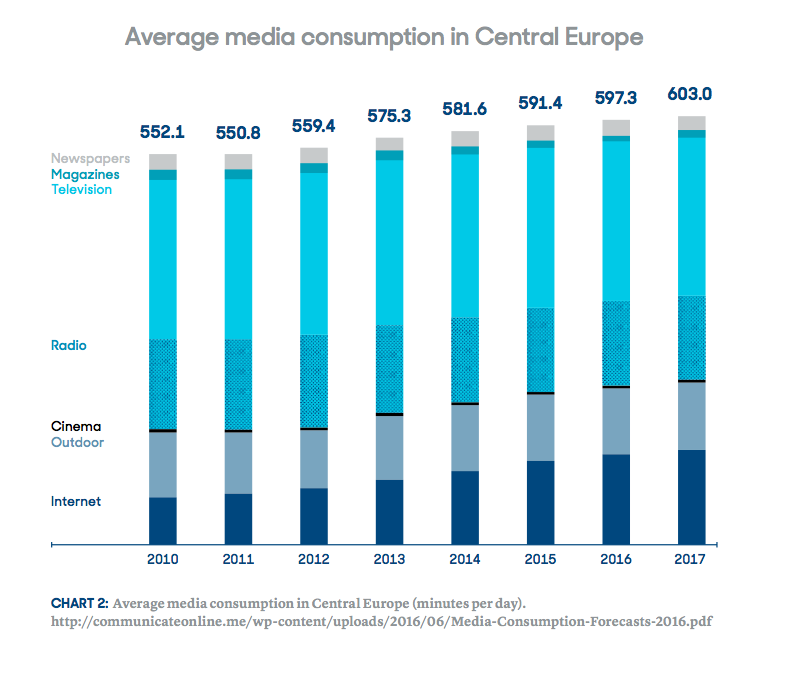

What is also reassuring, given the plummeting public trust in the media, is the way media are being used. Global data shows a continuous rise in media consumption year after year. This is the paradox of the times we live in: even if we do not trust something 100 percent, it does not necessarily mean that we won’t use it. And since media are nothing but a mirror of society, the trust they enjoy reflects society’s trust in the society as a whole, i.e. its trust in itself. Therefore we have no choice but to persevere in our efforts to improve this small part of the whole.