Jakub Dymek: In the early weeks of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Poland was internationally praised and celebrated for welcoming millions of refugees from the country of an attacked neighbor. Yet – as you relentlessly point out as both a humanitarian and member of the European Parliament – there are other refugees from other countries, who at the same time are stranded, mistreated and refused entry at the Polish-Belarussian border. My question is: why do feel it so necessary to remind the political class and the world at large about this discrepancy?

Janina Ochojska: The ‘why’ question is frankly quite obvious, at least for me it is. Every human being has certain inalienable rights. Violation of these rights equals lawlessness – unacceptable for me, for many in Poland, not least amongst them the activists who at this very time are busy saving people’s lives. This is all the better reason to irritate, to burden my political colleagues, with the knowledge of this.

We simply cannot accept, cannot allow for young people, children and families dying in the deep Polish forests and swamps, because we denied them entry on the basis of their religion, skin color and nationality.

The border wall Poland erected to stop the refugees is not working – not even in the narrow sense Polish authorities wanted it to work, because there are still people crossing the border and applying for asylum. And, of course, these people are illegally pushed back towards the Belarussian side, where some of them – beaten, starved, tortured – die. I once said how this brings to mind what was done to the victims of Nazi occupation during WWII – hunted, chased, arrested – and I do not regret this comparison.

Yet, you of all people, a humanitarian delivering aid to victims of conflicts, war crimes and catastrophes of all kinds, must be acutely aware of how strong these words are. You’ve yourself seen the consequences of horrific atrocities against civilians in the Balkans a quarter of a century ago. Yet, speaking of ‘genocide’ or ‘crimes against humanity’ is something one shouldn’t do lightly.

You can accuse me of abusing the word, sure. But we’ve discussed it, even recently, in the European Parliament: how many people have to be killed for a crime to be called a genocide? When and where are we justified in using the strongest of possible words of condemnation? For me, the numbers are not as important, to put it bluntly.

What is important, however, is the method of extermination that is being used against them. Is it systematic, is it deliberate, is it cruel – to take a refugee, to deny him/her asylum and then purposefully drive that person deep into the woods or swamplands and leave them there? We have witness statements claiming this is what is happening to families with children. There’s a video recording of border guards discussing such tactics between themselves. So, let me reiterate: it’s not about the numbers, it’s about the methods: torture, beatings, robbing people of phones, warm clothes, documents and backpacks. All of these serve a unified purpose: to deny right to asylum and prevent asylum-seekers from reaching a safe haven where their asylum application would be legally recognized.

I’ve used the word ‘genocide’ in the context of the Polish border with a full consciousness of it’s meaning.

Especially, when we already know what we condemn the Kurds, the Syrians, the Congolese to – when we deny them asylum or send them back to their abusers.

“Polish borders have to be secure, who does not understand this, does not understand what the word state means.” You know whose words these are?

The Polish PM or his cohort of security ministers, I’d presume…

Polskie granice muszą być szczelne i dobrze chronione. Kto to kwestionuje, nie rozumie, czym jest państwo. Ochrona nie polega na antyhumanitarnej propagandzie, tylko sprawnym działaniu. Za czasów PiS polską granicę przekroczyło rekordowo dużo nielegalnych migrantów.

— Donald Tusk (@donaldtusk) August 21, 2021

Donald Tusk, the leader of the European People’s Party, your party.

The thing is: I believe in secure borders too. But building a wall, torturing people, illegal pushbacks – this is not how you do it. I’d be happy to hear how Mr. Tusk imagines this. Because human rights violations aren’t helping us achieve this goal. Why aren’t the refugees using legal means of entering the country? Because those legal means have been denied to them. We’ve closed the legal ways of entering the country. We – as the EU – more and more often confuse ‘securing borders’ with ‘defending borders by all means’, regardless of their legality and basic common sense.

I’m asking you as an MEP. The EU decided a couple of years ago to externalize the refugee problem outside its borders, tasking various third parties, autocrats and warlords among them with keeping the refugees out. In hindsight, do you think this was the lesser of two evils, or simply an evil choice regardless?

I think it was a bad policy. If I was a Member of the European Parliament back then, I would have voted against these measures. Even if my political group in the EP did otherwise. Unfortunately, the ‘Fortress Europe’ mentality is growing stronger. Up until 2014-2015, the EU was way more open towards migrants and refugees.

I detest the policy of paying autocrats and foreign regimes for keeping refugees out and detaining them. We cannot stop migration this way, because there’s no way to stop migration. Humanity has migrated since the dawn of man. What I believe is: introducing legal ways of migration, aid to countries suffering from climate change, negotiation and a hardline stance towards aggressors, whose wonton violence – be it Syria, Yemen or Ukraine – is causing people to flee.

Can you give me an example of how this might work in practice?

What we, as Polish Humanitarian Action (PAH) did in Sudan for example, is a telling story. After building a 1,000 water wells, giving people ready access to fresh water, life and economic opportunities, hundreds of villages changed for the better. One can argue that a thousand water wells doesn’t change much in the whole of South Sudan. Sure. But these people aren’t fleeing to foreign countries, the people who benefited from these water wells are actively working on bettering life conditions for themselves and their families: building gardens, planting vegetables, improving farming and animal husbandry, not starving for once.

And as for legal migration?

I strongly believe in legal migration, which is necessary for our economies. But – let’s stick to Poland for a moment – after 24 February, nobody really cared to collect the data on arrivals, to asses who are those people, what are their qualifications, what languages they speak, how can we offer them the quickest possible adaptation and how can we, pardon the word, use them best in our society. This priceless knowledge had been completely neglected.

Exactly 30 years ago you initiated – alongside journalists, intellectuals and other respected people of the time – a humanitarian convoy to besieged Sarajevo, which later became the Polish Humanitarian Action, which is active to this day. Let me ask this question a little provocatively … Have you been bringing in weapons to the warzone?

No, of course not. [laughs]. I would not touch a weapon with a ten foot pole. And believe me, I checked every container on every truck back then.

„What is the best humanitarian aid for Ukraine? I’m sorry to say, but I say it’s weapons“ – is what Yevhenia Kravchuk, Ukraine’s governing party spokesperson and parliamentarian, sitting on Ukraine’s information policy and humanitarian aid committee, said recently to a Davos crowd.

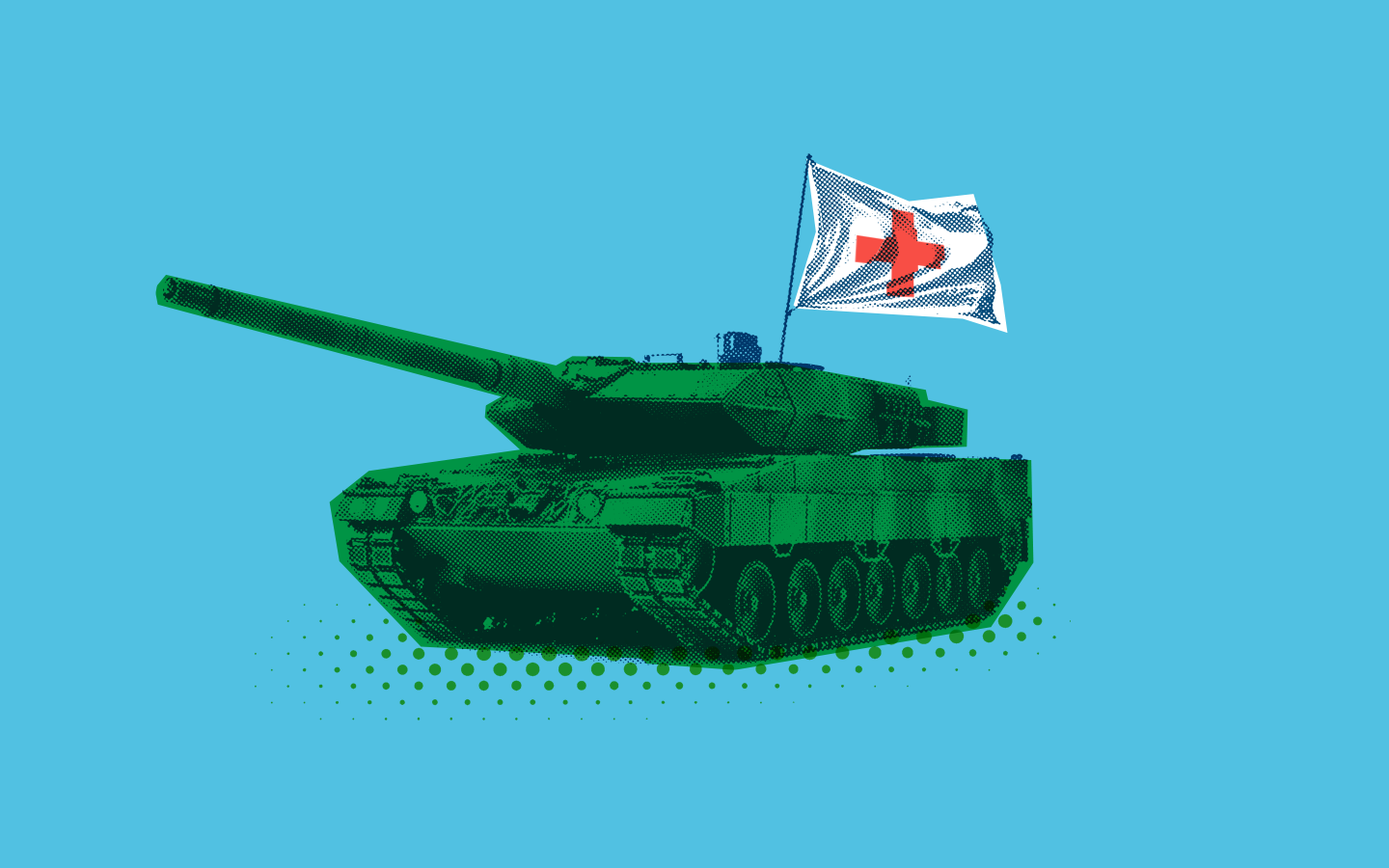

I would like to have an opportunity to talk to her and explain how humanitarian and military aid are two different things. These two things not only are separate issues, but they simply cannot be conflated into one under no circumstances! If we confuse one with the other, the very idea of humanitarian aid is at risk of being destroyed.

Of course, Poles nowadays are crowdfunding for weapons to be sent to Ukraine, buying an attack drone even! I refused to participate in these efforts. I’m a humanitarian, that is what I’m known for. Even if nobody mentioned my name, even if I was asked to do it anonymously, I refuse to support uncontrolled civilian efforts to buy arms. As a member of the European Parliament, I have always supported and voted in favor of efforts to control and monitor transfers of weapons. Either we have checks and balances or we don’t. Ukraine is no exception. The same as with humanitarianism – humanitarians don’t support armed forces with weapons, with food, with medicines. We help civilians, the victims of war, not provide backup for belligerent armies. This goes for Ukraine as well. The rules of humanitarian aid are very clear. So, again. Personally: I’m happy that this bayraktar drone will be bought in the end. But I could not participate.

Those who support crowdfunding of weapons are saying that refusal to buy more arms means war will last longer and more people will die. „Weapons will end the killing of people, which would be the best doctor, in my opinion“ – Fyodor Serdiuk, ex-Red Cross humanitarian from Ukraine puts it.

Weapons are for killing people. I’d like to ask those who say that refusal of crowdfunding for drones for Ukraine is the equivalent of accepting civilian slaughter. Why didn’t you buy a drone for Syrians? There’s been 11 years of war going on. Is this something you’re willing to accept? Are Syrian lives less worthy than Ukrainian? Is the slaughter of Syrians more acceptable? Or maybe you can kill Yemenis with more impunity, can you? People are being starved to death there. While we crowdfund for weapons for Ukraine, we at the same time accept the wars in Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan. Maybe we should have bought a drone for anti-taliban forces, shouldn’t we?

Everybody can use their money however they wish. They can buy Ukraine an attack drone too. It’s fine by me. But insisting this is the highest form of humanitarianism is a lie. I disagree with this ideology. “Help Ukraine, let the others die!” – is not my kind of humanitarianism.

Yevhenia Krachuk, the Ukrainian politician whom I cited previously, says in an interview with “The New Humanitarian”: “I don’t believe in neutrality, in our case, because you can’t be neutral to evil, you can’t be neutral to what we have in Ukraine.”

I agree that this is evil in its purest form, what is happening to civilians in Ukraine. But it isn’t some singular, ‘never-before’ evil. This is the same suffering that is being visited upon children and families in other countries as well. I understand what’s going on. Because of our proximity to this war, we feel we should be more involved than ever. Our organization has raised huge amounts of money for humanitarian aid, we have sent hundreds of transports with aid to Ukraine. We’re already planning on help with rebuilding Ukraine. One of the slogans I was thinking about was “30 schools for Ukraine for 30 years of Polish Humanitarian Action”. We’re already doing research into possibilities of that. We’ve been able to rebuild schools in Syria even, so I’m hopeful. We’re on the lookout for ambitious goals that are compatible with the humanitarian mission that we believe in.

But, let me reiterate.

As a humanitarian with decades of experience, I refuse to acknowledge Ukrainian victims as better in any way than any other victims of war worldwide.

This is against humanitarianism as such.

But you’re aware that just as we speak, the prevalent mood among European politicians and elites is exactly the opposite. What we’re hearing is that we have to turn a blind eye towards all the other war crimes, atrocities and civilian suffering, because now all other tyrants are our ‘allies’ against Vladimir Putin.

I do realize that. But this will not in any way change what I believe in. If you’re in league with murderers, you’ll lose eventually. I have never advocated against Russia as such, I do not consider Russia to be a country of evildoers and aggressors as such. It is the Russian elite. But I’ve never – contrary to almost all European, even Polish, politicians – courted Putin, believing he’s somebody to befriend, to appease. And I’ve never stained myself or our organization by being in cahoots with dictators. Unfortunately, it is still many people in the EU who did, and who let the dictators have their way – just name, besides Putin, Assad for one – time and time again. I believe what I believe, and will not change the definition, the very sense of humanitarianism, for short-term applause.