By Ann Markusen

People have been placemaking for millennia. Recently, new approaches position arts and culture center-stage. In creative placemaking, artists and cultural organizations play a lead role in community animation and economic revitalization by partnering with the public sector and other advocates and building on distinctive features of area culture. They often harness artistic skills to related local missions, such as transportation, health care, public safety, housing, environmental protection, and workforce development. Partnerships across public, private and nonprofit sectors, mission areas, and levels of government help to generate funding for initial investments and ongoing programming. Active participation by residents helps to ensure sustainability.

People have been placemaking for millennia. Recently, new approaches position arts and culture center-stage. In creative placemaking, artists and cultural organizations play a lead role in community animation and economic revitalization by partnering with the public sector and other advocates and building on distinctive features of area culture. They often harness artistic skills to related local missions, such as transportation, health care, public safety, housing, environmental protection, and workforce development. Partnerships across public, private and nonprofit sectors, mission areas, and levels of government help to generate funding for initial investments and ongoing programming. Active participation by residents helps to ensure sustainability.

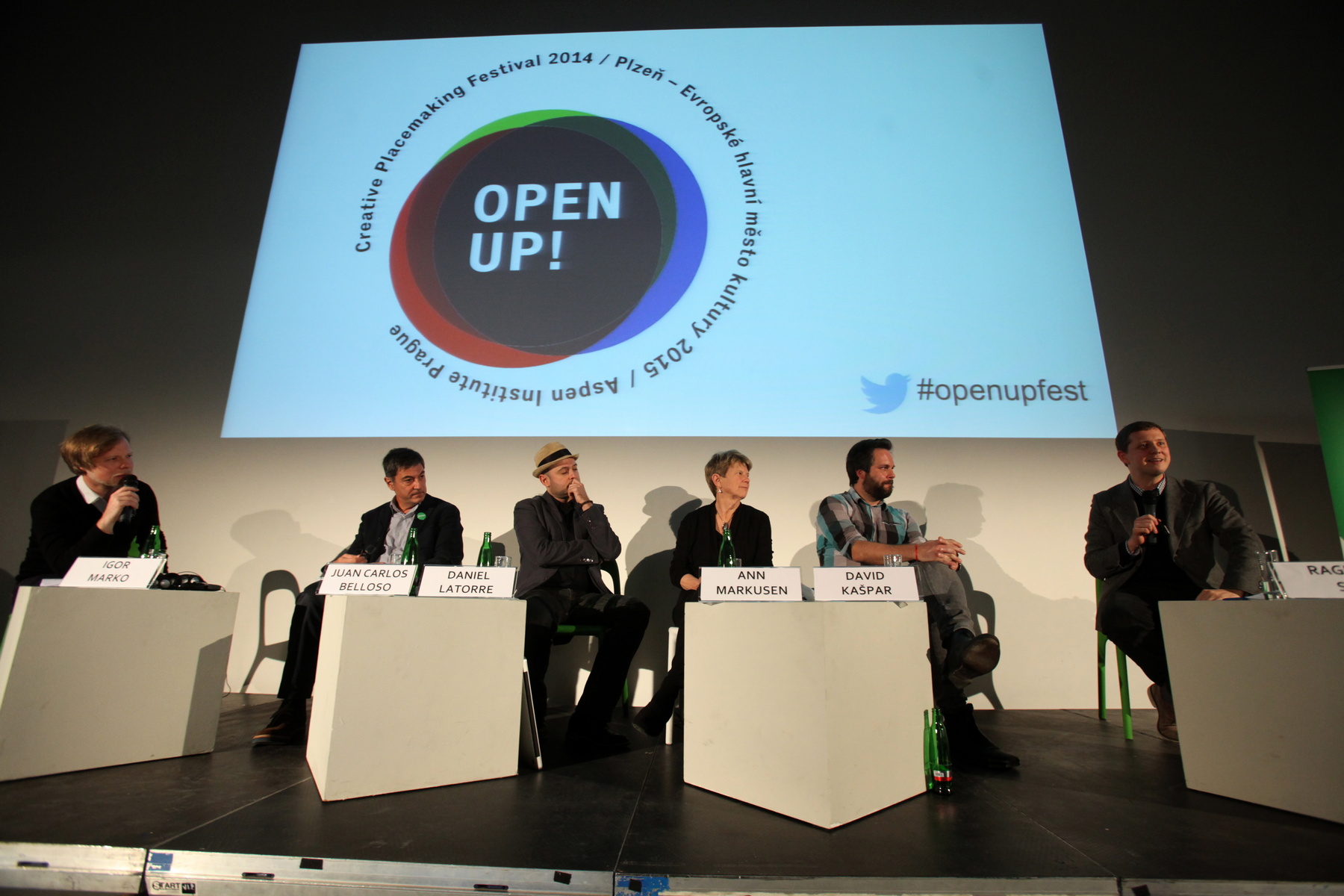

Anticipating Pilsen’s 2015 role as a European Capital of Culture, artists, arts leaders, public officials, community members, architects and designers gathered at the recent OPEN UP! events in Prague and Pilsen. Together, they explored how Pilsen, the Czech Republic, and Central Europe can capitalize on this opportunity to use arts and culture as a way of animating cities and neighborhoods, quickening economic development, and improving the quality of life. I was struck by the broad and energetic interest of participants, many of whom arrived from elsewhere in Central Europe, the existing experiments in creative placemaking that they shared with everyone, and their desire to build on both traditional and modern cultural movements in advancing their countries’ economic and social agendas. At the meetings, I shared my insights into creative placemaking in the US and listened to new ideas that I will be bringing back to North America.

CREATIVE PLACEMAKING INGREDIENTS

In a White Paper for the US National Endowment for the Arts, my colleague Anne Gadwa and I summarized the results of research we conducted on successful creative placemaking in the US. Our scan included large cities, suburban areas, small towns and Native American reservations; diverse arts forms (theatre, music, visual art, writing, design); and places that were in distress as well as those that were growing rapidly. Across the case studies, we found that most were initiated by a single person, often an artist, who had the vision and drive to pursue it. All tailored their creative placemaking around distinctive community features, from traditional culture to new artistic movements to unique landscapes. All had to mobilize public will, meaning a successful approach to the mayor and/or city council as well as generating interest among the area’s residents. All had to attract private sector interest and skills from developers, banks, and commercial businesses, and architects if new buildings or renovations were involved. All had to win support from local arts and cultural leaders who were often reluctant given their own agendas and struggles to raise funding.

PARTNERING

Nonprofit arts and cultural activities are often detached from public and commercial sectors. In creative placemaking, the framing rubric for the US National Endowment for the Arts’ new Our Town funding program, arts and cultural organizations are encouraged to partner with public sector agencies to initiate sustainable place-based projects. For instance, the City of Philadelphia’s mural arts program was created when an artist and her nonprofit, Philadelphia Mural Arts Advocates, approached the mayor thirty years ago to propose that youth and ex-offenders be taught painting and engaged to fill blank inner city wall spaces with murals in consultation with local residents. Today, many neighborhoods host beautiful and enduring murals, and even trash collection vehicles are beautified. Partners bring each other experiences, complementary skills, and greater visibility.

MISSION AREAS

Often, creative placemaking involves crossing mission areas. In the Philadelphia Mural Arts case, the city’s public safety, workforce development, and sanitation agencies supported the program because it enhanced their missions. In Portland, the public transit authority partnered with artists to design, in consultation with residents, what each new transit station would convey about the community. In Cleveland, a musician and several theatre companies hoping to restore two shuttered theatres and build a new one on the city’s working class west side found a willing partner in a community development corporation (CDC) that had successfully been building low income housing for thirty years. The CDC wanted to improve commercial business viability, and the theatre companies sought the CDC’s development experience and political connections. Together, they designed and built a streetscape that served as a launching pad for the Gordon Square Theater District and theatre renovation.

Often, creative placemaking involves crossing mission areas. In the Philadelphia Mural Arts case, the city’s public safety, workforce development, and sanitation agencies supported the program because it enhanced their missions. In Portland, the public transit authority partnered with artists to design, in consultation with residents, what each new transit station would convey about the community. In Cleveland, a musician and several theatre companies hoping to restore two shuttered theatres and build a new one on the city’s working class west side found a willing partner in a community development corporation (CDC) that had successfully been building low income housing for thirty years. The CDC wanted to improve commercial business viability, and the theatre companies sought the CDC’s development experience and political connections. Together, they designed and built a streetscape that served as a launching pad for the Gordon Square Theater District and theatre renovation.

FUNDING

Partnering and mission-sharing enable arts and cultural revitalization projects to raise adequate funding for both space investments and programming. In Cleveland’s Gordon Square Theatre District, the CDC’s connections helped the team raise their first $75,000 from the City of Cleveland and the Local Initiative Support Corporation. They then sought funding from city, regional, and state public agencies – the streetscape project required $3.5 million and took three years. The funds to renovate the theatres and build a new one required another seven years. As public funding commitments increased, the nonprofit foundations finally contributed as well, so that the team could tap into federal programs (historic preservation and new market tax credits). The Gordon Square partnership has produced sustained business improvement and greatly expanded the cultural offerings and participation in the neighborhood.

PARTICIPATION

The most successful creative placemaking projects involve community members actively from conception. Before the NEA’s initiative, local government chiefly funded public art projects commissioned, designed and built with no community input, resulting in often lifeless and sometimes publicly derided artifacts. Enduring initiatives actively engaged members of the public from the start, incorporating their skills, ideas, and dreams in the process. For instance, in Arnaudville, a small town in rural Louisiana, a visual artist with successful gallery representation in a large city elsewhere came home to live. He started a café that nurtures and showcases local artists and musicians, and builds on French language heritage, spoken by both Arcadian (Euro-American) and Creole (African-American) inhabitants. They have attracted artists and craftspeople to live there, started French language tables, and soon will convert their shuttered small hospital into a French language immersion school. Active engagement by people living in the Arnaudville area, whether amateurs or professionals, has been key to the art initiative’s success and contribution to housing and business revitalization.

SUSTAINABILITY

A key factor in sustainability, our research found, is to avoid “the edifice complex.” Over the past two decades, in North America, Europe, and Asia, local governments and funders (often prompted by funding streams like the UK Lottery Funds and European Structural Funds) have often over-invested in new or refurbished arts and cultural structures. Some have failed outright (Manchester’s Urbis, Sheffield’s National Center for Popular Music), because they provided ongoing staff and programming resources and their projections of attendance were far too optimistic. Right-sized structures that will be actively used, such as artist-live renovations, smaller theatre and gallery spaces, and artists’ centers run by membership nonprofit organizations that provide resources, equipment, teaching, learning, and exhibition opportunities, are more apt to be self-sustaining and animate the streets and neighborhoods where they are located. Where buildings are involved, funders and arts organization leaders, whether government or nonprofit, should take care to ensure adequate funding for programming and maintenance. Festivals, too, are problematic in that they engage local people and generate income and economic activity for a very short period.

governments and funders (often prompted by funding streams like the UK Lottery Funds and European Structural Funds) have often over-invested in new or refurbished arts and cultural structures. Some have failed outright (Manchester’s Urbis, Sheffield’s National Center for Popular Music), because they provided ongoing staff and programming resources and their projections of attendance were far too optimistic. Right-sized structures that will be actively used, such as artist-live renovations, smaller theatre and gallery spaces, and artists’ centers run by membership nonprofit organizations that provide resources, equipment, teaching, learning, and exhibition opportunities, are more apt to be self-sustaining and animate the streets and neighborhoods where they are located. Where buildings are involved, funders and arts organization leaders, whether government or nonprofit, should take care to ensure adequate funding for programming and maintenance. Festivals, too, are problematic in that they engage local people and generate income and economic activity for a very short period.

OUR TOWN AND ARTPLACE CREATIVE PLACEMAKING: US INITIATIVES

In the US, artists and cultural organizations suffered declining levels of public funding following the 1990s culture wars. Recent creative placemaking initiatives, however, are reversing that pattern. Since 2010, the National Endowment for the Arts’ Our Town program has granted over $21 million to teams of public and nonprofit partners, one of which must be an arts organization. ArtPlace America, a consortium of national foundations with bank partners and government agencies serving as strategic advisors, has invested $56.8 million in projects where artmaking improves community or place. The federal Departments of Housing and Urban Development and Education have revised funding guidelines to encourage arts-strategies in their programs.

OUTCOMES

Creative placemaking has multiple impacts, including increases in the quality of life, better and more jobs and income, and a broadening and deepening of the intrinsic contributions of the arts (beauty, delight, humor, innovation, social commentary, mirrors on ourselves and our society, carrying tradition forward, bridging across cultures). These are hard to measure in any conventional way. In the US, we have had an energetic debate about whether indicators based on secondary data can track creative placemaking success. For the most part, the debate has been won by the skeptics. The best evaluations do the hard work of determining whether the aspirations of the initiators, articulated in funding proposals, were indeed achieved in the project. In the US, the NEA and ArtPlace are creating cohorts of creative placemakers and writing up experiences as a way to provide models and improve practice.

RECOMMENDATIONS

For Pilsen, the Czech Republic and Central Europe, creative placemaking projects can improve on mistakes made elsewhere. Avoid expensive, new, and  over-sized structures – smaller, neighborhood, and community embedded spaces, often in repurposed existing buildings, are preferable. Avoid designated “cultural districts,” and the overconcentration of arts and cultural activities. Aspire rather for a mosaic that spreads across your city, region, and nation, with many distinctive offerings that will draw residents as well as those from elsewhere. Involve stakeholders in the process – local artists, retirees, high school kids, people with diverse skills and the willingness to devote time – rather than relying on architects and designers from elsewhere. Finally, plan for ongoing activities where artists and art lovers can work together on an ongoing basis to produce beautiful spaces expressive of the community, filled with many activities and all types of people.

over-sized structures – smaller, neighborhood, and community embedded spaces, often in repurposed existing buildings, are preferable. Avoid designated “cultural districts,” and the overconcentration of arts and cultural activities. Aspire rather for a mosaic that spreads across your city, region, and nation, with many distinctive offerings that will draw residents as well as those from elsewhere. Involve stakeholders in the process – local artists, retirees, high school kids, people with diverse skills and the willingness to devote time – rather than relying on architects and designers from elsewhere. Finally, plan for ongoing activities where artists and art lovers can work together on an ongoing basis to produce beautiful spaces expressive of the community, filled with many activities and all types of people.

Ann Markusen

Professor and Director Arts Economy Initiative

University of Minnesota